In 1992, a 25 year old Cameroonian filmmaker called Jean-Pierre Bekolo caught the attention of the global film audience with his maiden feature film Quartier Mozart which metaphorically explored self-affirmation and identity through feminine eyes. The refreshing tone of this cinematographic piece garnered positive reviews and acclaim in its wake, winning awards and nominations. Just like Les Saignantes, it featured women prominently and focused on moralistic concerns. It equally made the filmmaker a leading figure in national, continental and world filmmaking. Almost a quarter of a century and four feature films later, he has continued down the road of movie making.

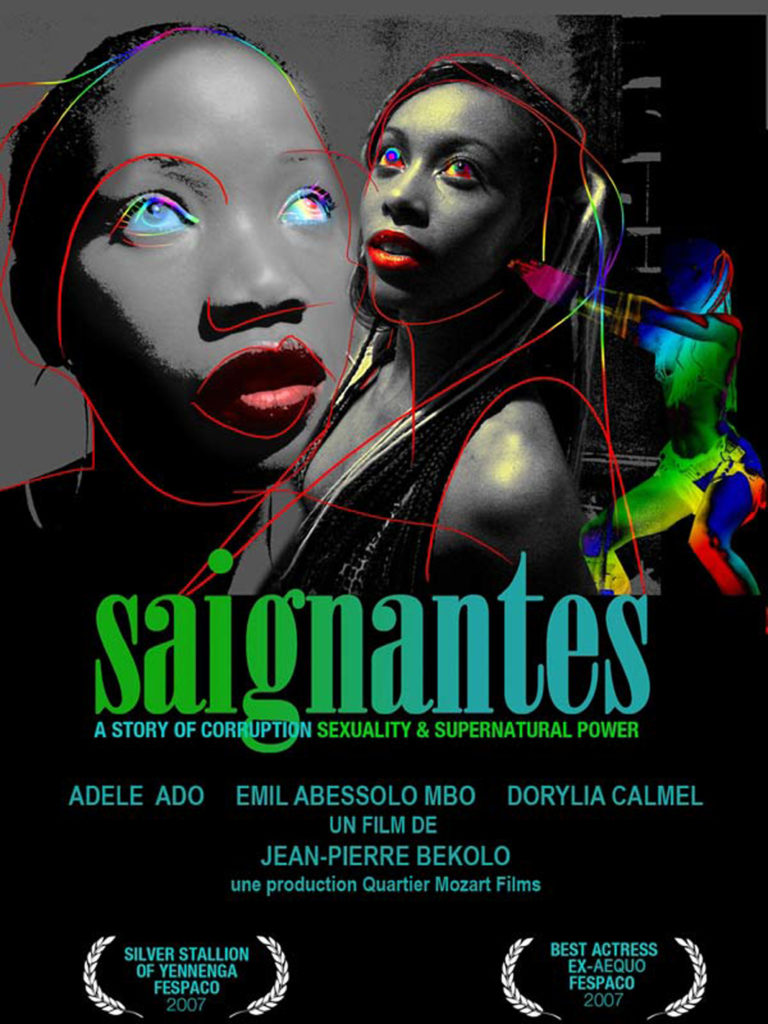

His controversial 2005 movie, Les Saignantes which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, grabbed numerous awards and has so far been variedly reviewed. One review describes it as a “…hybrid sci-fi action horror film…” This description betrays the multidimensional character of this film and readily hints at its uniqueness in the world of African cinema where the general monotony of storylines and chronic superficiality of movies produced has led to their consideration as “videography” not cinematography.

The Story

In simple terms, the movie can be considered as the energetic attempt of young women, Majoli (Adele Ado) and Chou-Chou (Dorylia Calmel), to cover up the accidental death, during sexual intercourse, of a highly-placed septuagenarian government official. The film is essentially a chronicle, set in perpetually stygian scenery, of their attempts to escape from this and other sticky situations created by the initial accidental death. To achieve this goal, they resort to every unorthodox means.

They find themselves locked in a cat-and-mouse situation with the police, fate, and conflicting interests. The movie’s hook lies in the uncertainty of whether their disposal enterprise will go unnoticed. This is the storyline in simple terms and it could be spellbinding for some. However besides its unique artistic value, the merits of this movie lie in its vast sociological relevance when viewed thematically and character-wise.

The Bloodlettes, as it has been translated into English, has a rich pool of themes that make the movie echo loudly as a reflection of Cameroonian society.

From the opening scene, sex appears as the leading issue as it notably sets the story in motion since it provides the context within which a government official dies. In fact it is the push that sets the movie’s ball rolling, it is also an indication of the moral pulse of the characters in particular and society in general. The pervasiveness of the practice portrays the moral bankruptcy dogging society. The only way the women can get a contract to supply trucks is by having sex with the Secretary General of the Civil Cabinet who dies in the process. When Chou-Chou tells the cab driver to drive slowly and to keep moving on, he immediately equates these statements to having sex [“fucking” in his own words, as he says “…Are we in the middle of fu…fu…fucking or what…? ’Cause…if that’s the case… I can always find a more comfortable place…]. He even threatens her with rape when she reacts angrily to his implicit sexual solicitation.

With an African society as a backdrop, the recurrence of sexually-laden scenes, the uncensored display of feminine nakedness and body parts like women’s breasts, not forgetting the rhythmic choreography added to sex scenes which all team up to splash the film’s narrative with a keenly erotic if not pornographic shade, account for its highly controversial nature, especially given that Majolie’s choreographic aerial movements in the opening scene during her deadly romance with the SGCC are reminiscent of a dominatrix.

Sex is not just a sign of moral decadence but also a tool for showing the central and domineering role of women in inter gender situations. All through the film, they take the lead during the act by either being on top, negotiating the terms or surviving it whereas their male counterparts are underneath, don’t initiate its commencement, die from it and do not negotiate its terms. Sex thus becomes an arena where women can and do prevail over men during any head-on confrontation. Sex, thus comes off as a currency, a “soft currency” of sorts, to be precise, in the socio-political life of the women, who are financially weak, to get what they want from the men who are financially strong. With this in mind, one can thus wonder whether the film’s director is not a “closeted feminist” who uses his heroines through their almost dogmatic recourse to sex to endorse the most extreme constructs feminism has offered so far. By having his leads consistently use sex to bargain, isn’t the director faintly advocating slogans like “My body, my choice.”

Another relevant issue is inter-generational conflict as exemplified by the relationship between the young and the old, especially between the young police officer on the one hand and the old police officer on the other hand. Although the young and old share the same geographical space,they do not share the same vision or perception of things. In fact a visionary and existential divide can be said to exist between them and this is shown not necessarily through open conflict but through questions from one aimed at the other and a consistent difference in opinion. The young officer indirectly questions his senior colleague’s habit of drinking while on duty by asking him, “How many beers are we allowed drinking on duty?” When the elderly Inspector stops a car and accepts a bribe to let the car go unchecked, his young colleague insists on checking the trunk.

At one point, while the young police officer thinks of informing the Minister of State about the dangers threatening the republic, his older colleague questions the existence of one and rather wants to eat and drink without forgetting to mention that they are lots of pretty women. The young police officer disapproves of this attitude by wishing him good appetite.Their Training Day-like tandem suggests a circumstantial unity but shows a perceptual divide, as earlier stated, that augurs crisis in the near future.

Inter-generational conflict traverses the film’s entire narrative, manifesting itself most evidently in oppositions between characters of the same sex. Chou-Chou and her mother’s cult just like the elderly Inspector and his colleague are ideologically opposed as well. Doctor Amanga and Majolie /Chou-Chou are also in conflict but theirs isn’t ideological. Their conflict is fuelled by opposing interests, while the former wants to monopolise the Minister of State with whom she is already sexually involved, Majoile/Chou-Chou want to the snatch him from Dr Amanga’s grip in order to lobby for lucrative government contracts. This puts them at loggerheads right from their first meeting at the mortuary and during their next encounter at the SGCC’s wake keeping.

In this cinematographic comment on social decay, corruption is undoubtedly another overarching issue. It is present in the usual places like between the police and car drivers. When stopped, Majolie prepares a CFA 1000 note which she gives to the elderly Inspector when he questions them about the car’s ownership.

It is as well noticed in unusual and macabre places like the mortuary where the mortuary attendant demands CFA 100,000 to fake a corpse by fitting the SGCC’s head to a different body. It is equally evident when the butcher is given money to accept that what he is butchering is beef although he has discovered that it is human flesh after tasting a slice. These last two scenes particularly attest to the extent of corruption and affirm that it does not only affect the living but also the dead.

For all its credits, this movie also has a number of faults that dent it considerably, if not severely.

The film is littered with a series of questions that pop up on a billboard as the storyline progresses. Some of them are “How can one make an action movie in a country where acting is subversive?”, “How can you film a love story where love is impossible?” ,“How can you make a crime film in a country where investigation is forbidden?” Although it is understood that these questions further consolidate the underlying social activist stance of the move, their sudden appearance distorts the normal viewing experience which is supposed to be straight and uninterrupted.

Furthermore, if a movie’s storyline is considered as discourse, aren’t these visual interjections in some way belabouring the point? If this movie is an outcry against all the ills contained therein, then these pop-up questions are unnecessary reminders of issues that are highlighted with words and images. This begs the inquiry whether a question on a billboard can better drive home a message than a scene where visuals and words are used.

The abundant presence of a cryptic entity like Mevoungou, steeped in symbolism, does not only add depth to the movie. It also, and rather unfortunately, strains and even confuses the average viewer who ends up not knowing whether Mevoungou is a person, a spirit, nominal representation of vice, value or some tribal god. This is all the more true given the rather confusing reference to Mevoungou in the film when it is said that “We had to use Mevoungou and get rid of it quickly if we wanted to survive”. The role of Chou-Chou’s mother and her side women is equally confusing as the occultist tone that accompanies their various cameos leaves one wondering as to what they represent: high-priestesses of Mevoungou or elderly and calm overemphasised side-kicks to the young and exuberant leads.

On account of its symbolic depth, the Les Saignantes is not an easily accessible movie as too much para-visual and para-cognitive material is required for comprehensively grasping the complete girth and depth of the movie. A case in point is the “Scream” poster in Chou-Chou’s bedroom. It hints at the underlying horror dimension of the movie but this fact is lost to any viewer who does know about the relevance of the movie Scream in horror movie culture.

Petty inconsistencies like the colour of the cab boarded by Chou-Chou and actual colour of taxis in Cameroon where the film is apparently set also question the film’s realism.

Given the movie’s various layers, it is possible for it to be variously described. It can be considered a social comment on survival in a morally-challenged society, given that for all their weaknesses, the leads are merely trying to find the light at the end of a dark tunnel in which fate has put them. Labelling this movie an ode to extremist feminism is equally possible as Majolie and Chou-Chou are emancipated and strong-willed women who assert themselves albeit immorally and bravely accept the consequences. Although she comes into the film secondarily, Chou-Chou exemplifies this more strongly as she tells Majolie, who thinks they are “…just two helpless women.”, that there’s “Nothing wrong with being a woman” and that “No one’s gonna screw me” when Majolie adds that they are “just two holes that always get screwed in the end”. Such deep reflections do not just reinforce the feminist side of their characters but adds depth to their characters which otherwise would seem nothing more than burgeoning escorts, thrill-seeking bitches or gold-diggers. These moments are a welcome distraction for these two whose humanity seems extensively marked by sex, mischief, immorality, more mischief, and sex.

From the hitherto description, this movie can seem a boring lecture on experimentation in cinematography but it is worth stating that it contains moments of levity and why not comedy. It is quite funny to hear one of the leads describe the wakekeeping for the SGCC’s corpse as a “good wake” because there was food amongst others. Hearing the elderly Inspector tell his young colleague that whether or not they are not allowed to drink on duty depends on the generosity of the car driver before them can be a light-hearted moment in a film that can be considered an exaggeratingly pessimistic and almost apocalyptic portrayal of society given that the movie is shot only at night and vice overwhelmingly overpowers virtue since even the latter must be used to record petite victories over the former.

However, for all its pessimism and attempts at optimism, sex, nakedness, eroticism, cannibalism and ideological feuding, this movie is above all quite frightful not because of the cannibalistic butcher and the goose-bumb provoking thought of a corpse- mutilating mortuary attendant standing over your body with an axe. No, not at all. It is fundamentally frightful because it reads as an informed disenchanting forecast about a country seeking to be an emerging country. After watching this movie, the question that immediately comes to mind is whether or not a country dogged by such ills can ever emerge. This is a hard-to-answer question. The moon setting at the end can be interpreted as a note of optimism in a long pessimistic concerto. But then again how can this be reconciled with the young policeman – the film’s only beacon of hope in this sea of desperation— letting Majolie/Chou-Chou escape with their spoils and laying down the Inspector’s gun, with which he was investigating? Isn’t this a strong hint that vice will ultimately win even if virtue puts in overtime? These possibly contradictory outcomes make it hard to attribute one generic label to the movie. But then again, what if it is described as the energetic attempt of two escorts to escape from their situation by fucking their way up? Seriously-speaking and in simple terms, this movie as a social comment is music to the ears of doomsayers and a requiem to those with high hopes for the future of the country referenced in the movie.

Nchanji M. Njamnsi is a translator, freelance journalist and blogger

Join the Twitter discussion of this review of Les Saignantes by using the hashtag #LesSaignantes when you weet and see what others are saying

Don’t forget to follow @BakwaMag on Twitter