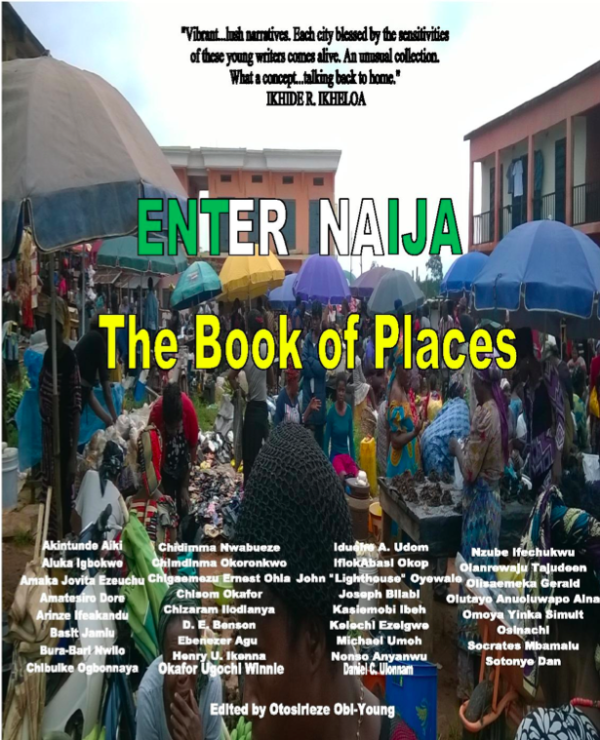

A day after October 1 2016, Brittle Paper released an anthology, “Enter Naija: The Book of Places”, in celebration of Nigeria’s 56th Independence anniversary. The book is a collection of stories, poetry, non-fiction and photography all focused on a particular place in Nigeria. Uzoma Ihejirika speaks with the book’s editor, Otosirieze Obi-Young, about the book and a host of other issues in the literary world.

Congratulations on ‘Enter Naija: The Book of Places’. How has the reception for the book been so far?

Thank you, Uzoma. The reception has been beautiful so far. A lot of people are impressed with what we did. Three people have written me about how inspired and encouraged they now are to continue pursuing their different projects.

Reading the book opened up a lot of experiences to me, the good, the bad, and the in-between of life as a Nigerian. What informed your decision to create such a book?

Firstly, there was the travelling factor. I don’t travel much so our National Youth Service in Akure was my third time out of the East and my first time in Yoruba land. I was hooked by the sprawling topography, green hills and dark rocks. We often took walks to take photos. It also surprised me that some Akure indigenes seemed oblivious of the fact that their city is beautiful. And then there was Gossamer: Valentine Stories, 2016, a free anthology edited by Nonso Anyanwu. After it came out in February, I began thinking of doing something similar, asking people to send writings and photos about places that matter to them.

In the context of literature, what does ‘place’ mean to you?

Literature can make a seemingly plain concept like ‘place’ become one with inexhaustible meanings. The sort of magic Teju Cole centers in his fiction. For the project, place is simply geographical location. Where the contributors cared enough to write about or photograph or create visual art about. And because place can mean various things to various people, the approaches taken in exploring place in the anthology vary. Most of the writers focus on physical description; some mix this with character analyses of their populations; a few romanticize their places; a fewer number have personal stories tied to their places; one person takes a semi-historiographical approach; two or so highlight the music and food of their places; and the rest of us tackle identity, how living in a particular place shaped how positively or negatively people regarded others. But it wasn’t enough for us to merely discuss places, we wanted to render those places as urgent characters, places that are as unforgettable as they are familiar. The ones you read about and imagine visiting.

The anthology, according to the book critic Ikhide Ikheloa, is ‘a gathering of unsung, young but vibrant writers’. Was it a deliberate act on your part to feature young and emergent writers?

No, it wasn’t deliberate. Partly because I was focused on their contributions rather than the authors. I wanted good writing and photos and visual art and it didn’t cross my mind whether or not the authors are ‘emerging’ or ‘established’. Writers often categorized as ’emergent’ can pull out show-stopping pieces and ‘established’ writers can turn out average stuff so it just didn’t matter to me. I made a call for submissions on Facebook and writers responded with submissions that are impressive. However, I did ask one Established Writer, a Caine Prize winner, for a blurb, which he couldn’t give due to the short time frame.

Also, Ikhide knows what he’s talking about when he writes ‘unsung’. Not ‘unproven’, but ‘unsung’. The contributors, like I pointed out in the anthology’s Editorial, have among them a slew of award wins and nominations and acclaim and literary projects and books published. And so ‘unsung’—publicity—might just be the difference between some of the contributors and some Established Writers.

You’re a writer of short stories and essays and are obviously used to submitting your works to magazines and journals and waiting upon the response of an editor. Now, in your role as an editor, how was the shift for you? Any challenges?

LOL! The shift!

I wanted it to be as interactive as possible and I certainly didn’t want anybody waiting for anything—it’s not The New Yorker. I tried my best to reply submissions within hours, to read them once they appeared and reply the authors, so we often went to and fro until the submissions were shaped to fit in with the rest.

I contacted Ainehi Edoro of Brittle Paper who was instantly supportive. Then Nonso Anyanwu linked me up with Nancy Adimora of Afreada who was extremely helpful, as was Chukwuebuka Ibeh of Dwartsonline and the Expound and Praxis teams. I also had to ask Ikhide Ikheloa to write the Introduction, a natural choice because he’s a solid champion of young talent, and he graciously agreed and did something so lovely and quotable. A few writers—contributors and non-contributors—also made suggestions. So with all these people getting involved to different extents, there was far more help than challenges, and that is what matters the most, that more than a few people were willing to help see this happen.

I believe Enter Naija is ‘the first in a series of anthologies…that would explore different aspects of Nigerianness’, so would you be kind enough to let us in on what themes you hope to explore?

There are so many subjects to be explored in Naija, so many that merely contemplating where to continue from could be overwhelming. I have it all laid out, only considering now which would come next and when. Hopefully, it would be in progress before mid-February of next year. We’ll have a deluxe edition of Enter Naija in 2017, something beyond a PDF anthology, a collection of narratives from different media.

Let’s divert a bit. In your essay, ‘Imperialism-in-Artistry: Bob Dylan’s Nobel Win Is Proof Adichie Is Right about Beyonce’, published on Brittle Paper, you made a startling observation that it seems there is a hideous attempt to get ‘literary prowess to “bow down” to musical prowess’. You strengthened this belief on the fact of Adichie condemning efforts to get her to ‘perform expectations of gratefulness to Beyonce for sampling her work’. Don’t you think it’s all just a mere coincidence, that there might not be anything for lovers of literature to be scared about? Or do you still stand your ground?

If by ‘coincidence’ you’re referring to the fact that the Chimamanda-Beyonce talk and Dylan’s win happened close to each other, then it is. But if “coincidence” refers to the fact that, in two consecutive situations, musicians have been given priority over writers even in a literary context, then of course I think that there is every reason to be worried. Music might be more glamorous than literature in pop culture but it will continue to be condescension to expect writers to defer to musicians when both contribute equally to shaping our world.

Nigerian writer Chigozie Obioma in his article for Guardian UK has made a case against provincialism. He advocated that a writer should spare nothing to see to it that his readers get vivid descriptions of a place or items of a place. This he highlighted in saying that molue would read better as ‘a beat-up squeaking yellow-painted bus with a constant metallic rattle’ rather than just simply writing molue. What’s your take on this?

Firstly, I love that Chigozie Obioma is staking a claim to be considered our most fiery essayist. His arguments are resonant. But I really develop a headache whenever this Who Do Africans Write For argument resurfaces. The thing has so many links to other arguments about literary poverty porn and Africa Should Not Be Explained and Africa Is Not a Country and Western Publishers Dictate to African Writers and Don’t Italicize Local Words and even Afropolitanism, all of which result from the singular, seminal horror that was colonialism. Aminatta Forna, Ben Okri, Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, Taiye Selasi, and now Obioma have taken this from varying angles. But every argument and counter argument simply adds to this policing which has, admittedly, ultimately proved itself necessary. I think it was in a conversation involving NoViolet Bulawayo or Chinelo Okparanta or both that it came up how Africans spend time tearing each other apart. So while we need to tell those stories of ourselves primarily to ourselves, we cannot deny that we also need to tell those stories to others, retell what they have always told the world about us. We have been colonized and, to forge ahead, we must compromise. It is illusion to think we can’t compromise when our political systems here are in shambles: there is a glaring, direct link between political efficiency and artistic freedom. Only when we fix our political and economic institutions can we successfully reject compromise. For now, for us, it can only be the middle ground. But certainly not extreme middle ground where poor, innocent molue will be described and “shown” to an extent where it can no longer be recognized by its very owners. Truth is: star writers like Obioma have earned a bit of leverage and can persuade their editors to risk a few things, and it is primarily—often only—our star authors who have visibility who can shape this development.

Let me ask this: Who exactly is Otosirieze Obi-Young?

He’s just one of those boys. The kind of bobo who stares at a fallen palm tree because he seems to think it’s beautiful. Rumour has it he’s also a romantic. And that he also envies physicists and mathematicians.