As a prelude to Bakwa 08, the “Pain” issue, we’ll feature two stories which capture the mood of the issue. The first is a story of longing by Ucheoma Onwutuebe.

1

Love was a sturdy man arriving on countless evenings at my doorstep, looking like the aftermath of a hurricane, reeking of beer and earthiness and the stench of the world outside. With his laptop bag slung over one shoulder, and a glint in his eyes, he would ask, “Did you miss me?” I always let him in. Who was I not to? I would bury my nose in the crook of his neck, and stay there till he tickled me away.

I am yet to find anyone who smells half as heady, half as good.

2

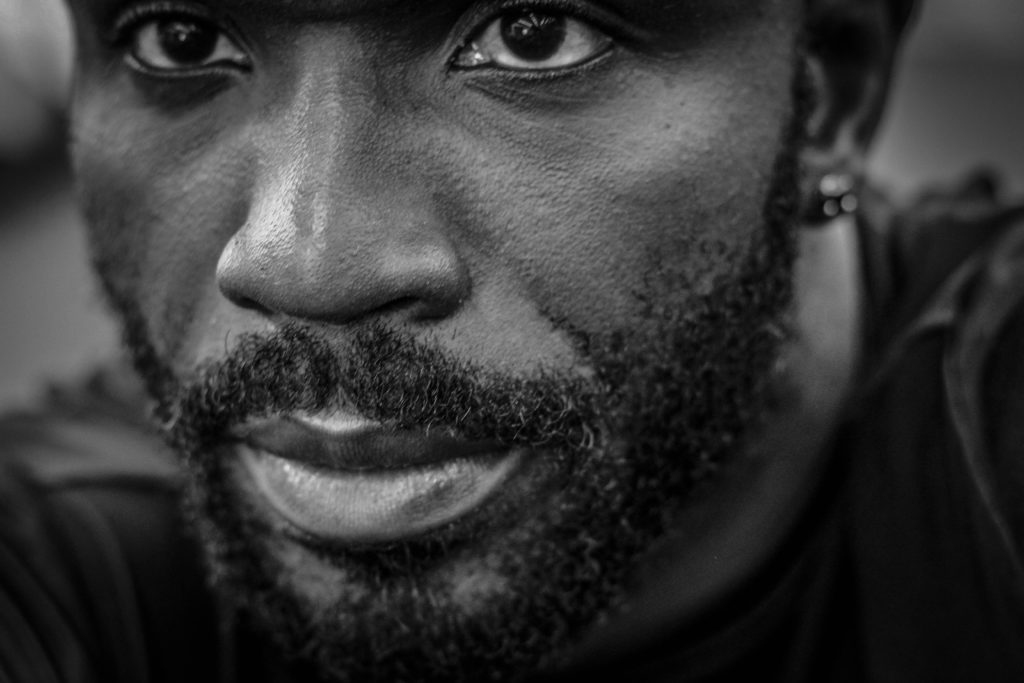

Nothing in his mien gave away his profession. A scientist was supposed to carry himself with an air of carefulness and a precision associated with measuring things. But not this man. Not this scientist. I was sure his beard would one day be singed by the fire from his welding machine. His jeans were ripped, his hair shaggy. But his hands were strong. I had watched him on several occasions bend metals to compliance, and on those countless evenings I let him in, he showed off the gashes his skin had sustained during work, from welding pieces of iron together, or screwing a nut under a machine. He showed them off like a war man’s wounds, an old soldier’s decorations. Those nights he came to me, I too, like those malleable metals, became pliant in his hands.

3

On countless evenings, I cradled his head in my hands, took long draughts from his lips, laid his head on my lap and fondled his shaggy beard. Those nights I was Helen of Troy; I was Herodias with the head of John; I was Delilah stroking Samson’s mane. I thought, This man whose hands bent metals, who stood before a class of eager students instructing them, on whom much of their success depended; this big man who shouldered his way through life, navigating his path with cunning and a deep voice, was he all mine?

4

In those days I found work as an entry-level bank clerk, and I spent my days among colleagues, with whom I had formed a strong bond –the way people who suffer together form a comradeship in the midst of their struggle. We were excited to see each other most mornings, but by evening, we were so pensive balancing our books and looking for missing tellers that we could not stand each other. The job offered the advantage of a steady income, but it was not without the drudgery of standing all day, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. It was a job founded on capitalism: whatever profit we made was enjoyed by the higher powers which we did not see. But we showed up every day regardless. Most days we were grateful for work, other days we were full of angst and regret. I and the other junior clerks talked of resigning and finding work elsewhere, but we never found the courage to do so. We had unemployed friends who wished to be in our place, and their envy and longing made us hold on tighter to this job that no longer met our needs.

But my evenings were not entirely hopeless. Even if I was frazzled and spent, I knew in whose company I would find my recovery. If he and I had planned a rendezvous, those last few minutes to the close of work would have me looking at the time, willing it to tick faster, urging my colleagues to hurry up –it was against company policy to leave anyone behind. Such evenings, anticipation made me a tethered canine whimpering for release, a tied horse neighing for the fields. I could not wait to be with my man.

5

“Should I read to you?” he would ask. He picked up Julius Caesar, dramatising as he read. Before then I had never paid heed to Shakespeare, even though I claimed to be a writer. Shakespeare’s King James language gave me a headache. Why read him when I could read Achebe and Ekwensi, writers who blended the English language till it sounded like my mother tongue? But it was he, my sturdy man, who let me in on the lyrical beauty of Shakespeare’s works. It could be raining heavily, or maybe a slight evening drizzle— my zinc roof exaggerated the sounds of each, making it hard to tell whether it was rain or drizzle–, and yet he would read to me.

That was not the first time someone read to me. My mother did when I was a child; she read to my siblings and me from the Ladybird Series, and she told us of how she read to her grandfather many years ago in his last days when his sight had deserted him. She was a girl then, sent to live in the village with her grandparents who she took care of. Her grandfather, a devout Christian, listened to her read the Psalms, and in listening to her voice, he prepared his soul for the bosom of the Lord.

I had come to view reading to another person as an act of affection— towards children too young to decipher text, and towards adults who had gone blind. But with my man I experienced reading as a romantic sport. When he read to me, the lilt of his voice soothed me and lulled me to sleep. His favourite lines were:

Danger knows full well that Caesar is more

dangerous than he. We are two lions litter’d

in one day and I the elder and more terrible.

He would read these lines, his voice rising, as if he was on a stage, as if he was Caesar. Why did those lines appeal to him so much? Did he know, just like everyone did, that he carried about him a whiff of danger? When people saw us together, they looked at me from the corner of their eyes, perhaps thinking, “What is this good-natured girl doing with this type of man? Can she deal with what comes with this?” They looked at me the same way when they saw me sitting beside him at Picnics, the open space bar opposite the university, watching him drag his stout from the bottle— he never used a tumbler, said it stood in his way. But I knew what the onlookers didn’t know: I was the whistle that brought this racing stallion to a halt; I was the hand that tamed the mane of this lion.

6

It was the smoking which he did openly, that gave him the whiff of danger. The university town we lived in was a temperate one, and smoking held the aura of criminality for most of its people. Ironically, this worked in my favour. This was my mind, howbeit naive: not all women here can stand a man with such airs. They would only skitter in and skitter out, incapable of bearing with his ways. And in accepting him in all his flawed glory I had marked him for myself.

7

The nights he refused to come to me, especially in the first few months of our affair, those nights had me upset in ways I am too shamed now to describe. In love, there is always a more desperate partner and that partner was me. If he cancelled our rendezvous using work or tiredness or some incapability as excuse, my evening was ruined; I did not know then how to take disappointments well, and nothing could quench the fires of my pining. I began to think of devices to pull him closer to me. I lined the corners of my house with cigarettes: I kept packs in the lowest bedside drawers and covered them with books so no one would notice. I hid some in the highest shelf of the kitchen counter, in my handbags kept in the wardrobe, in any secret corner I could find.

Perhaps this was selfish, but I did it anyway. Didn’t everyone he knew– his mother, father, church brothers, church sisters–urge him to stop? Didn’t they all preach the gospel of “smokers are liable to die young”? But here I was, smitten beyond recognition, bent on sticking by him no matter what. Whenever he came over to my house, our little trysting place, I offered him a pack. The first time I did, he looked at me with suspense, perhaps gauging me, trying to be certain I was ready to be complicit of his habits. But, over time, my offering and his subsequent smoking became a routine of our meetings.

The first day I went to the kiosk to buy a pack, the little salesgirl looked at me sceptically; I knew she was judging me. I could read the disappointment in her mind: “What is this bespectacled girl doing with a pack of Bensons?” I did not flinch under her gaze. I paid for the cigarettes like I would pay for a pack of sugar. Or soap. Or toilet rolls. I held the pack in my pocket; it would bring my lover closer to me, bring him home more often.

8

What is a love affair without a theme song? You do not think of Titanic without remembering the flute and violin warble and Celine Dion’s vocal accompaniment.

John Legend’s ‘This Time’ was it for us. It answered my frequent question: “Do you love me?” I could be in a corner sulking because he had dismissed something I said or he had judged me wrongly over a matter, and, noticing my mood, he would play ‘This Time’ from his Blackberry, and gather me in his arms. He would sing along with gusto just like he did everything else. “This time I want it all, this time I want it all, showing you all the cards, giving you all my heart.” Isn’t it the little gestures that make our hearts trip and fall hard again and again?

Maybe this too was maudlin, but it held deep meaning for me. The lyrics of the song brought back the memories of the first time we ever had a conversation. We were with mutual friends in a hot restaurant on a Sunday afternoon. I had met him just a few hours before, but our talk was lively. I do not remember what steered our conversation to this angle, but I had casually asked him about his stance on love. He said he was not given to it. “Women come and go,” he said. And when they tired of his noncommittal ways, they left and told him to go marry his machines.

So when he sang that song to me, I felt— he didn’t say so, this was my private interpretation— that he wanted to stay, that the era of flimsy affairs was over. He did not say so, he did not need to say the words to me; it was all there in the way he gathered me in his arms and sang to me. What’s more, we were going on a year and several months. And at each instance, whatever the need was, he sang to me.

9

“You are my kryptonite,” he said.

“I love you,” I said.

But I am broken. Can’t you see?

Desire loosens the tongue. Ask Delilah. It was not folly that brought Samson back, again, and again, and again, to her doorstep when it was plain as day that all she wanted was to deliver him into the hands of his enemies. It was not folly that made him sleep off each time she stroked his mane demanding, “Tell me the secret of your great strength and how you can be tied up and subdued.”

Desire. Desire. Desire.

My sturdy man told me many things that had left him broken in those nights he showed up, in the dark hours he whispered to me. I wanted to rewrite every painful tale he told and kiss it away. A loss too painful to heal and forget? I kissed him. The days in the past when fortune deluded him? I kissed him. I wanted to fix the memories. I wonder who told me kisses could mend leaking spaces. The only experience I had with mending broken vessels was from childhood, when I had to cross the streets with the other children in the compound to fetch water with jerry cans and ferry them home in wheelbarrows. Often, we dropped the containers too hard on the floor and they cracked. Sometimes the puncture was small enough to be patched with chewing gum; sometimes gum could not hold it together. And, in those times gum failed to mend the broken can, we would heat a knife in fire and smear the hot blade on the crack, and with a sizzling sound, the heat would melt the rubber and hold it in place, filling the air with an acrid smell.

With the quiet sounds of kisses, I wanted to mend him. How I wanted my machinations to work. How I wanted to mend him. But each day I saw him, met him in our small corner, our little world of passion and longing, I lay content in his arms. It did not matter how broken he was. I did not want to be anywhere else.

10

This is my favourite memory of my lover and me. One evening, we sat huddled in a corner of a thatch-roofed bar, a joint different from the one close to the university. Surrounding us were beered-up men having spirited conversations. The football match was making no headway and almost over, and there was general disgruntlement in the air. He lifted his bottle of stout to my lips, urging me to take a sip, then he whispered to me about a new spot where the suya was fresh and the beef was today’s butchered meat. We headed there and, on our way, I don’t remember what he said, but he filled my lungs with laughter and caused me to throw back my head and show my teeth to the moon. In his roadside shop, we watched the suya man stoke his fires as he barbecued the skewered meat, sprinkling spices on them. We ate straight from the newspapers and the pepper made me cry. He laughed at me and pulled me closer and said, “You’re such a baby”.

11

I loved my lover then, I love him now still. I loved him because his lust could not be contained. On some nights out, in the middle of a conversation at a table full of mutual friends, while we were all presumably lost in banter— and the talk had veered into politics, football, or any of those topics that rouse young people– and the equal complement of alcohol laid before us had loosened everyone’s tongue, my lover would whisper to me, “Meet me in the car, I want to touch you”. Sometimes, if the car was too far away, he would take me to a corner far from peering eyes and touch me, and in those quick but charged moments, he would be as bestial as he would be tender. His lust would possess him like a demon and, until he had found reprieve, he would not be still. It drove him like a full bowel desperate to be emptied. Those date nights, we would have to make an early exit, leaving our friends behind and driving home silently.

And in those silent, pregnant moments, we would speed past people laughing and talking; past twinkling streetlights that could not sustain their lights due to age or vandalism; past stores with blaring TV sets; past carefree children who play in the streets.

In those moments, the car became misty with the thoughts of passion and reckless abandon as we headed to our place, mine or his; thoughts so tactile they formed a third presence in our midst. His hand sat gently on my laps and, with certainty, I knew: in no time, these hands of his that lie idly on my laps will rove, and roam, and feel the warmth of my body. These clothes on my back, these shoes on my feet, will all, in a moment, be heaped on the floor. This mouth of mine that says nothing, and this voice that is now silent and tucked away somewhere in my stomach, will say unspeakable things. And my body that sits so tamely in this car will no longer be mine alone. It will be bent in curves and arches, and I will move it in unfathomable ways.

And the very thought of this, the anticipation of lovemaking, would make the two moulds of my breast rise, would cause moisture to gather warmly between my legs. And the tension would keep brewing as we stood by the door while he held up the torch of his phone as I scrambled in my bag for my bunch of keys; I would feel the tension as he tucked my braids behind my ears when they fell over my face as I kept ransacking, all the while standing so close to me that I would hear his breathing, hard and steady. Then the keys would turn in their holes and we would shut the door behind us….

12

These days when distance has thrown a chasm between us, I carry his memory around me. I bear it about me: in the hollow of my clavicles where he has poured his kisses, in the dimples of my buttocks where he has drilled his name. I bear him in my pouch like a kangaroo carries her young. Every indention of my body, every pore craves him. On countless nights his memory lulls me to sleep: memories of being bent over, memories of the black of his skin glistening in coital perspiration. He has loved me so hard I am hypnotised; I do not remember clearly anyone before him. Do they even exist? Every love I’ve had before now has become hazy, chaff. I am not even interested in making anyone from my past envious; all that matters are those memories of riding on the crest of emotions with this man.

Some nights, I wish I can fete myself for a possible séance with him in my dreams. Some nights his smell haunts me and starts me from sleep.

“Study Man with Shaggy Beard” is from Bakwa 08:PAIN

The second and final story of the two-part prelude to Bakwa 08, the “Pain issue” is “How to learn a Language”

Ucheoma Onwutuebe is a Nigerian writer whose work has appeared in Brittle Paper, Prairie Schooner, Lip Magazine Australia, Sentinel Nigeria, Y!Naija and a bevy of other outlets. She blogs at www.ucheomaonwutuebe.blogspot.com.