Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed

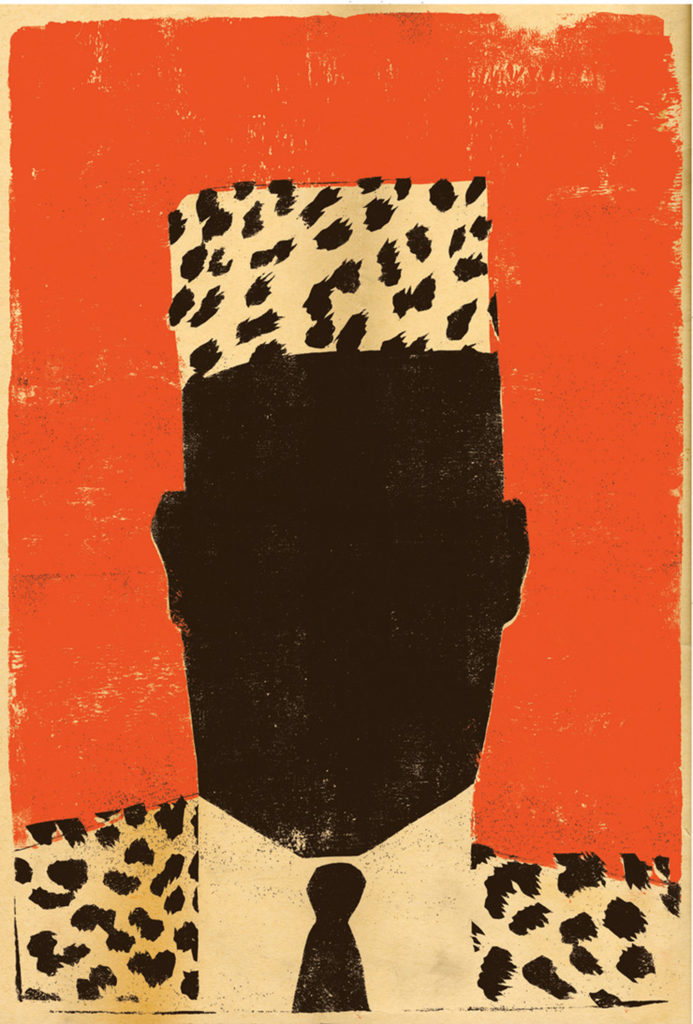

Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed explores the presence of nameless narrators in African Fiction, highlighting some of the most memorable nameless characters as they explore colonial and postcolonial rule, immigrant experience and love.

In the beginning of March, The New Yorker published “The Rise of the Nameless Narrator”, in which Sam Sacks explores how in recent years novelists have not been “naming their creations.” He lists “an epidemic of namelessness” already published in 2015 from Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island to Alejandro Zambra’s My Documents; goes into the world of fairy tales with Sleeping Beauty and The Little Mermaid and of course, mentions some of the most memorable unnamed characters in literature— Dostoevsky’s Underground Man and Ellison’s Invisible Man.

As a lover of African literature, I was extremely excited to see two literary works by African authors mentioned in this article— Teju Cole’s (2007) semi-autobiographical novella Every Day Is for the Thief and Dinaw Mengestu’s (2014) “fiction of exile” All Our Names. Well, if you are curious about what other nameless narrators can be found in African literature, here’s a look at some of them.

Back in 1954, The African Child (L’Enfant noir [1953]) by Guinean author, Camara Laye was translated into English by James Kirkup. A semi-autobiographical tale told in the first-person, The African Child’s narrator remains nameless for much of the novel. It explores this nameless narrator’s transition from an African child raised in the mountainous areas of Guinea, to him moving to the capital city of Conakry and becoming more French. Moving to Equatorial Guinea, Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel’s By Night the Mountain Burns (2004)— translated by Jethro Soutar— recounts the nameless narrator’s childhood on a remote island off the coast of Equatorial Guinea, while in Domata Ndongo-Bidyogo’s historical novel, Shadows of Your Black Memory (2007) (Las Tinieblas de tu memoria Negra)— translated by Michael Ugarte— a nameless child narrator also reflects on his childhood during the last years of Spanish rule in Equatorial Guinea.

Sudanese writer, Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North (1966) translated from Arabic by Denys Johnson-Davies, charts through the experiences of its two central characters— one a nameless narrator, who has recently returned to Sudan after many years studying in England. Another tale of the ‘returnee’ comes from the nameless narrator of Tanzanian author Abdulrazak Gurnah’s Admiring Silence (1996). Gurnah’s unnamed narrator escapes Zanzibar to England, where he ends up living for twenty years with an Englishwoman. He eventually returns to Zanzibar only to be confronted with a different country.

In his 1978 book, The House of Hunger, Dambudzo Marechera’s story opens with the nameless narrator leaving the “The House of Hunger”. Set in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe today), the nameless narrator traces his life in a nonlinear way. Another Zimbabwean author, who has a nameless narrator is Brian Chikwava, winner of the 2004 Caine Prize with his short story “Seventh Street Alchemy”. His debut novel, Harare North (2009), is told from the perspective of a nameless Zimbabwean living as an illegal immigrant in London. Still on the theme of immigration, Harvard Square (2013), Egyptian writer André Aciman’s third novel, recounts the time spent by a nameless immigrant graduate student of Comparative Literature at Harvard.

South African writer, Nadine Gordimer’s short story “The Ultimate Safari”, first published in Granta in 1989 and later included in her 1991 collection, Jump and Other Stories, follows the story of a young nameless narrator and her family as they leave their Mozambique village for a refugee camp across the border in South Africa. Another short story with a nameless narrator is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Birdsong”— originally published in the September 20, 2010 issue of The New Yorker— about a career woman living Lagos who falls in love with married man.

There’s also Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968), which tells the story of a nameless narrator simply called The Man, who works at a railway station in Ghana and struggles to not become corrupt. Yet another nameless narrator can be found in Room 207 (2011) by South African Kgebetli Moele. Set in and around a dilapidated building in Hillbrow, Room 207 goes into the world of six young men who have lived in this one room for over 10 years. They are Matome, Molamo, Zulu-boy, D’nice, Modishi and the nameless narrator. Another story set in Hillbrow, comes from South African author, Phaswane Mpe. In his debut novel Welcome to Our Hillbrow (2001), the nameless narrator leads the reader through the main character’s life in Hillbrow.

Finally, not content with one narrator, Ivorian Véronique Tadjo’s novella, As the Crow Flies (2001), explores the individual loves and lives of nameless characters living in unknown locations.

Clearly, this is not an exhaustive list of all nameless narrators in African fiction, but from exploring childhood under colonial and post-colonial rule, to the immigrant experience and even love (in its various forms) namelessness seems to also be quite prevalent in African literature.

Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed is a Researcher at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, and (hoping) to soon be done with her PhD at the London School of Economics. When she’s not doing either of those, she’s blogging about her true love – African literature – at bookshy.