Wirndzerem G. Barfee

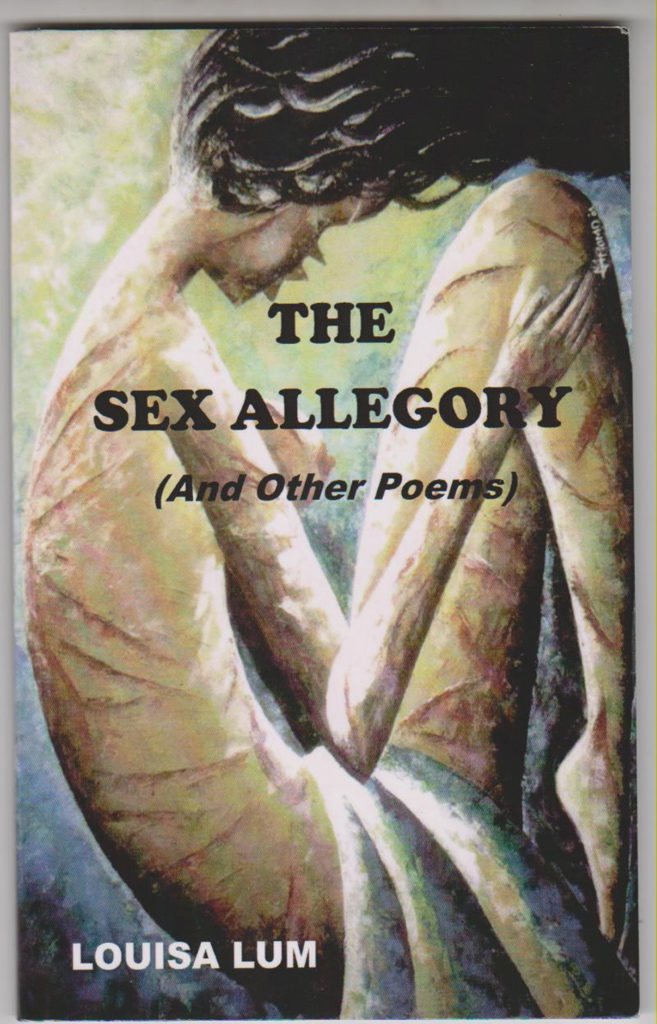

One of the first things that after strikes the sensibility of a sensitive reader is the originality of a book’s title. When it comes to poetry; that exigency is doubled. Lum Louisa, on this critical count, succeeds in a superlative manner to coin a title that tallies both originality and critical pertinence when she baptises her collection as The Sex Allegory, the title of an eponymous poem therein included.

The Sex Allegory. Why the sex allegory? Why the sex? Why the allegory? Allegory is simply defined as an extended metaphor. And the poet in her title stretches the metaphor of sex on a triptych frame: 1) sex as gender politics between man and women, 2) sex as power politics between the ruling class and the ruled, 3) sex as a socio-carnal rapport playing on sensuality and sexuality (through seduction, carnal license and suitoring). Going through the 34 elegant poems; the perceptive reader will appreciably understand the stylistic ramification of the title as pointing to sex here as a rapport; a relationship of power, emotions and attitudes. Sex, hence, in Lum Louisa’s collection becomes a terrain or site where the actions and actors of gender, politics, morality, sexuality, sensuality, and materialism interact and operate to re-orient a new order and vision guided by the descriptive and prescriptive purposes of the poet.

This new order and vision, as compassed by the The Sex Allegory and Other Poems, charts an ambitious range of facets and depths in the exploration of power, emotions and motivational dynamics that drives her project. The extensive gamut of this ambition has been condignly appreciated in the preface by Labang Oscar as being characterised by a variety of styles and subjects. In same variegated vein, another reviewer, Dzekashu MacViban in characterising the poems has exclaimed that “the poems are outrageous, challenging, radical, cynical and funny…[and] are so different that one wonders if it is the same book we’ve been reading all along!” These categories of variety include the liberal and universal; the local and global; the moral and the mundane – all underpinned by the humanism and politicality of the poet’s ideological inclinations.

Within this sensitive variety and diversity of poems, sub-groups emerge and they do not emerge as hermetic containers or insular tanks. They surface with a configuration of osmotic and imbricated parts that intelligibly communicate with each other to form a dynamic and integrated poetic organism. These major sub-groups or parts that readily chapterise themselves into recognisable aggregates include poems that predominantly deal with:

1) power politics (politics as we know it);

2) gender politics (the man vs woman politics);

3) materialism and the cult of the apparent;

4) morality and motivational poetry;

5) the local and the global (or globalisation);

6) the poetics of sensuality and sexuality.

I. Poetics of Power Politics

My curious readings of most poetry written by most women Anglophone writers, especially the younger generation, has consistently indicated an intriguing avoidance of strictly political verse, especially the radical indictment or protest strain. They rather have the flair and preference for sentimental or feminist poetry, a fact that has been saluted in some critical quarters as a welcome relief from the political overkill of the male (or men) writers. Lum Louisa breaks with this a political tradition by questioning and indicting political powers – and this she executes with remarkable brilliance through the apt use satire, sarcasm and innuendo. Hear her poem “Head of Heads” satirize African heads of state and their penchant for excessive presidentialist Jacobinism and pathological nepotism:

If wishes were horses

I will become a president, an African president

Because I will be the law

I will be head of everything that needs heading

Head of armed forces,

[Head] of party,

[Head] of state,

Head of heads. (p-6)

Again, she skilfully uses tongue-in-cheek innuendo to stretch this indictment in poems like “Laws” where we read:

A leader changed the constitution

He consulted no one but the good lord

…..

L’état c’est lui même!

The law must favour its maker. (p.12)

Other political poem “Your Excellency” (p.12) and “Puppet Masters” (p.30) are more brutal in their indictment of power and high office holders in a state where ministers even thank the president for the air they breathe. Her politics as earlier indicated naturally and significantly extends to gender politics.

II. Poetics of Gender Politics

From the title and cover graphics; the immediate connotations we stitch are those of gender politics and issues through, as indicated, they go beyond and deeper than that surface, the towering import of this genre of politics in the collection receives a wide and varied concern and address. The feminist fist is controversially raised then criticised at same breath with a healthy paradoxality that spawns no sterile contradictions. For instance, The Sex Allegory poems engages us in the war of the sexes especially in the eponymous poem itself, a very solid, tight wholesome poem that introduces us – through Chinua Achebe’s proverbialism – into the flux of gender rivalries where men and women run to out-do each other in a race :

What a flux

Men and women wish

To out run each other in a race.

Men want something for free:

…………………………..

Ladies know men have learned

The shooting trade so well,

……………………………..

[And women] Have learned the flying game too,

And practice to filch grains in mid-flight. (p.15)

The poem “Man versus Woman” continues this man/woman opposition but from a critically contentious paradigm: that of gender essentialism. This is evident when the persona sententiously purports that “what makes a man is / The alacrity in the man / And what makes a woman is / the aura in the woman” (p.10). In other less essentialist dimensions, she proceeds in a more trenchant fashion tomake strong, assertive and revendicative political and cultural statements regarding the position of women in a man’s world. This is eloquent in the poem “Suitors” where the courted female persona dismisses the gendered, objectifying flattery and differential labelling by the male poet-suitor and does this with an assertive claim and impression of un-complexed gender competition:

I am a poet just like you and not

A poetess, I won’t be your muse.

If anything, I will be your mentor

You put me in a place I strive to surpass

You go with the claim we are the weaker

…………………………………………………………

I know your intentions, I will not be enslaved. (p.36)

In an intriguing ambivalence the feminist author does not tarry to engage an antithetical lambast of pseudo-feminists who are always blaming the man while thriving on the counter-productive crab-mentality of holding each other down in the basket. This is what she does in “These Feminist Clowns”. And hear her:

We are feminist clowns…who

Chatter like weaverbirds, making grand schemes

Of how to kill the man and rule the world;

But no concrete solutions.

…………………………………..

For who holds the woman down to mutilate

But another woman;

Who connives with men to bring another strong woman down

But another woman?

……………………………………..

Real feminists know their strength

They don’t need to wear trousers to show they are strong. (p.40).

In her shifting range of objective portrayals, the poet in “Cougar Victim” (p.43), also engages a stimulating execution of what we can define here as reverse hegemonic genderism where man, in the sex game, becomes the weak prey and woman, the strong predator.

To these dualistic feminist poems can be added, one of my treasured picks of the collection – “Point of Attraction” – a poem at treats feminist and other pertinent themes with an assertive happy-go-lucky hilarity, verve and suaveness that leaves the song singing in your mind long after you had closed the book.

III. Poetics of Moralization and Motivation

The poet in this collection does not only take on the political and patriarchal powers that be. She also takes on the society at large engaging a poetics of social critique and moral re-armament. This is individually and variously directed at women and girls regarding their excessive consumerist and materialist penchants, their unabashed and instrumented sexuality and sensuality as seen in “Point of Attraction” where in the church the lady takes a vantage position for eye contact and even with her long skirt, she can still rear the end, her fatal point of attraction to seduce the pastor and other prosperous brothers. She also moralizes university dons who have lost their sense of purpose and vocation and have become the grotesque and ribald butts of ethical reprimand. This is seen in “Dons Playing Politics” where she urges dons to:

Leave politics to politicians…

It is not your place

To make a fool of the great institutions of learning

……………………………………………

Leave politics to politicians,

You can’t be at peace

With a few francs that exchange hands,

Like thirty pieces of silver,

This time not to sell another,

But to kill your own conscience. (p.42)

And still to dons on a ribald note, she adds in “Suitors” that the teacher….Like a de-mentor,/He feeds on fear and pounces when the target is weak…..And doles out sexually transmitted marks (STM’s) like a Good Samaritan “over-ruled by the little fool he nurses between his legs”. (p.38)

She does not spare the philandering sugar daddies whose bellies compete only with their wallets…yes, pot-bellied money bags who play helpless romantics. (p.39), the handsome, narcissistic players and heartbreakers too, they pass through the lashing and are levied an indemnity for the heart transplants needed by those unfortunate girls who crossed their paths. In the poem “Wanting” The persona does not spare herself a moralizing auto-critique for her materialist propensities, always insatiably wanting and craving mundane things even when their acquisition and possession is dangerous for her intrinsic well-being. (p.3)

But after excoriating the society she heals it with motivational poetry as seen in “Weight of the World” where she urges the reader never to lose faith in self even when the world is against him (p.5) and “Poverty” where blessed are the relatively deprived. (p.11)

IV. Materialism and Cult of the Apparent

On no point else does the poet deftly combine critique and humour as on the twin themes of materialism and the cult of the apparent or artifice. What her keen feminist eye sees with crystal lucidity her pen paints with unparalleled hilarity. And these can be found in poems like “Chic Madam” who is a cool fashion icon with trends too expensive to follow, a queen of glam who carries tons of false hair on her head, wears all high heels until they begin to hurt, lightens her skin until she defies race classification; she even becomes an artificial Barbie doll (pp. 31-32)., more poems like “Wanting”, “Nip/tuck” p-28 and “Beauty in a Bottle” (p.27) that takes an array of materialistic cravings for forbidden, tantalizing things, the desire for clothes, shoes, make-up and all sorts of apparel that will make women dressed-to-kill builds up the theme of materialism imbricates fluidly into that of the cult of the apparent or of artifice marked by an unbridled and obsessive longing for and worship of all that appears to be and not what is. This is seen in “Beauty in a Bottle”, where beauty is seen to come but from the mascara box of make-up and false faces. Seen again in “Nip/tuck” where beauty is procured at all costs from plastic surgeons and readymade shops until the excesses transform beauty to Frankenstein’s bride – an allusion to the tragic plastic surgery addiction of Jocelyn Wildenstein who has allegedly spent over the years almost US $4,000,000 on self-destructive cosmetic surgery. We are left with a cast of misfits and the alienated who worship the artificial, the superficial and the superfluous as constitutions of reality and beauty.

V. The Local and the Global: Glocalisations

The poet in this rich collection demonstrates an informed mixture of the local and the global. This is seen in the local coloration of language and tropes especially in the poem “Point of Attraction” and “Chic Madam” where she offers a delicious blend of the local parlance that is fluently and fluidly weaved with English. She also delves into the actuality of the global relating local political conditions with the recent Arab Spring uprisings in “Your Excellency” p-13. She poeticises grand ambitions, the T.B. Joshua and other Pentecostalist phenomena that make currency on our present socio-cultural landscape. It is thus a poetry steeped in actuality and currency on a global and local space and time.

VI. Sexuality and Sensuality

There is a decent disappointment (and for obvious reasons of abashment when it comes to our cultural treatment carnal sex. As such that the author navigates indirectly around in an informed avoidance of the handling of physical sexual act. She leaves such issues at the limits of seduction and courtship. But she compensates such erotic deficits with an arresting imaging of sensuality, especially her takes on feminine seduction for moral and predatory purposes that crystallize into a sort of sensual seduction as power in the women folk. “Point of Attraction” and “Sex Allegory” epitomise fittingly this seduction power, as pointed in earlier sections of this review.

Conclusion

This review is just a tip of an impressive poetic iceberg, with so much still to explore under the waters. But I will not end without pointing at some low points in the work. They are stylistic and editorial. Though the poet manifests great sparks of skill in most poems, one still finds that some or parts of poems fail to ring with the same brilliant consistency. The major turn-off points include the pathological fixation onmatter to the detriment of manner, an over focalisation on message to the defeat of music. On these counts “Man vs Woman”, “Poverty”, “The Fool”, “What a World”, amongst a few disappointingly exemplifies this pattern as we find in it more of a lecture, a manifesto than a poem. In same line, the motivational poems fail through their pedagogic and sermonic tones that make the writing more a coaching class or a sermon, and less an aesthetic enterprise.

Editorially more than a dozen spelling, grammatical and semantic were counted and included errors like swap for swoop, gape-toothed for gap–toothed, live for leave, waver for weaver and wreck for wreak.

These errors dampened in no way the reader’s relish for the poetic output of the young, debutant and promising author, Lum Louisa. I read the collection back to back and front to sides and jealously wished I had written two of my very favourite poems in the collection “Point of Attraction” and “Suitors” – those two poetic gems are overwhelmingly hilarious and profound.

Wirndzerem G. Barfee is the author of a poetry collection titled Bird of the Oracular Verb (winner of the 2011 EduArt Bate Besong Award), he has published poems and essays in literature and culture in publications such as Palapala Magazine, AfricanWriters.com, Saraba, Sentinel Poetry Quaterly, Fabafriq and Conversation Poetry. He has also been involved in editorial projects which include Songs for Tomorrow anthology (Miraclaire, 2009), Ngoh Kuoh Review (Miraclaire, 2011) and Eco-Salvation poetry anthology (Miraclaire, 2011).