Who is Imbolo Mbue? What does it mean to write a million-dollar novel? Nkiacha Atemkeng explores these questions and reviews “Emke“, Imbolo Mbue’s first published story.

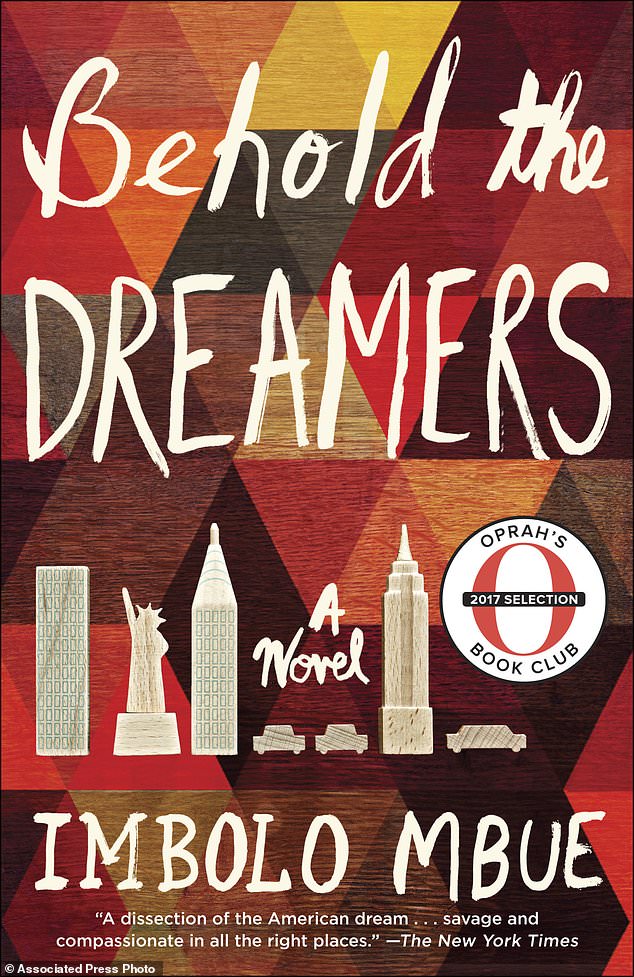

When I first heard that a US-based writer from Cameroon, Imbolo Mbue, had signed a whooping book deal of one million dollars for her manuscript, The Longings of Jende Jonga (the title was later changed to Behold the Dreamers) at the 2014 Frankfurt Book Fair with the prestigious publisher Random House, I was really elated. For a first-time novelist from the coastal resort city of Limbe in Cameroon— which is not as big as Nigeria or South Africa on the African literary map— to sign such a mammoth book contract was quite an achievement two years ago and will always be.

I tried to google her name since I’d never heard about her and found almost nothing. This made her book deal more stunning and, to a certain extent, even mythical. Up to the age of 32, she had no publishing history, whether in print or online, which one could jump on and read as an aperitif for the upcoming novel. She had no blog and no personal profile on any social media platform. (I later learnt she has a phobia for social media). Dibussi Tande recounts, in a story in an article some months ago, that he couldn’t even find a single photo of her online. So who was this mythical Harper Lee-like million-dollar author from Cameroon called Imbolo Mbue? She was so unknown in the literary circles both in America and Africa that acclaimed writer, Jacqueline Woodson, started her appraisal of Imbolo’s hitherto unknown talent thus, “Who is this Imbolo Mbue and where has she been hiding? Her writing is startlingly beautiful, thoughtful, and both timely and timeless.”

Well, maybe Imbolo wouldn’t even have ever written any fiction. In fact, she has said that, even though she has been a lifelong reader, she had never considered writing until she read the brilliant novel, Song of Solomon, by the acclaimed 1993 Nobel Prize winning American novelist, Toni Morrison. She loved the novel so much that she picked up her pen after she finished it and became a wordsmith. Anxious readers and new Imbolo fans finally got a taste of her craftsmanship in her first published short story, “Emke” available for free online on the Threepenny Review. The story is set in America as is her just published debut novel. I think Imbolo will be writing a lot of immigrant literature. This will probably not be very god news for us Cameroonians as we would love to read her Cameroon set stories and ponder on her musings of her motherland.

She was so unknown in the literary circles both in America and Africa that acclaimed writer, Jacqueline Woodson, started her appraisal of Imbolo’s hitherto unknown talent thus, “Who is this Imbolo Mbue and where has she been hiding? Her writing is startlingly beautiful, thoughtful, and both timely and timeless.”

Imbolo travelled to the US in 1998 when she was sixteen just like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Chinelo Okparanta, and NoViolet Bulawayo, who also left for America as teenagers. She studied at Rutgers and Columbia Universities. So these questions will always linger in my mind: How does the diaspora influence Imbolo’s writing? Does she write “to get back to Africa”, like Tope Folarin once said on BBC when he was asked why he writes? Or does her work reflect that state of flux between America and Africa like Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, which fluctuates between America and India? Here is what Jonathan Franzen writes of the author: “Imbolo Mbue would be a formidable storyteller anywhere, in any language. It’s our good luck that she and her stories are American”.

Her first published work is a short story titled “Emke”, whose title is derived from the main character’s name. It relates the life of an African man, probably Sierra Leonean, who is extremely ill and, in the writer’s words, has “a disease of the blood” in a US hospital. This may probably be leukemia. He suffers from nightmares but maintains hope, “a frail optimism”, and then finally dies. The story is so real it comes alive on the page. It has the ability to evoke memories of your own deceased loved ones. Imbolo knows about dying, rather she knows how to write about dying. Her imagery on the subject is so vivid that you dread your own dying day. At some point, Imbolo presents her readers with a taste of Ben Okri-like magical realism:

After he had toweled off, he would tell us about the nightmares. In one, he was given a glass of blood by a hand without a body, and asked by a baby’s voice to drink it all in one sip. In another, he saw his head on a tray, laughing at him.

There are various issues highlighted in “Emke” such as illness, healthcare, politics, treatment, death and burial. Imbolo’s characters, though very few in this story, are well rounded. Her writing style is simple, clear, and very concise. Her economy of words is remarkable, especially in this tale. It is such that I describe “Emke” as a “short-short story”. The piece is so terse. While you are in the groove with its pretty lines, it just stops and is simply over! Poet Mp Mbutoh writes about its brevity thus, “But perhaps its briefness makes it all the more memorable, just like an interrupted French kiss!”

At just 1400 words, it is not eligible for a Caine Prize submission!

Questions will always linger in my mind: How does the diaspora influence Imbolo’s writing? Does she write “to get back to Africa”, like Tope Folarin once said on BBC when he was asked why he writes? Or does her work reflect that state of flux between America and Africa like Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, which fluctuates between America and India?

Imbolo’s language is beautifully unique and is at times reminiscent of Toni Morrison because of the way she pays attention to language, imagery, and poetry in her writing. Below are some excerpts:

He knew that blood is the river of the body and with his being contaminated, his body might soon shrivel up and die like plants on a dried river bank… His disease sat between us, like an August forest fire, burning away. With every glance at him my heart enlarged, overcome at the beauty he was even in his state of ugliness… Emke lay frozen with a grin, wearing a suit he would never have chosen for himself, packed in an ice box for the five-legged journey.

Nevertheless, I felt “Emke” was too predictable. I guessed the whole plot and it didn’t deviate from what I was imagining all through, thus the element of surprise was missing for me. I wanted Imbolo to take me to some other place I wasn’t expecting. But the twists and turns weren’t there. Is it because the story was too short for such explorations?

Furthermore, I didn’t quite agree with the political views of Imbolo’s character. Emke’s political utterances didn’t go down well with me. Take the following excerpt …The talk about the future of Africa resting on the institution of exemplary democracies amused him. Such fancy Western ideologies will never take root among our people, he often said… Why such pessimism? It can take root. Yes, many African countries have leadership problems and there have been many dismal failures, but some nations have shown good democratic track records like Ghana, Tanzania, and Botswana. Nigeria has discarded brutish military dictatorships for democratic civilian rule for sixteen years now. Though, I admit, even those good examples still have problems. But then, is America’s democracy perfect? Also, many western countries have practiced democracy for about 500 years. Meanwhile many independent African nations have been practicing democracy for just over fifty years. They’ll slowly get there.

This other statement caught my attention and I also disagree, What we need back at home isn’t some absurd imported idea of government but a chance to live in good health and govern ourselves as we see fit.

However, “Emke” is overall a solid short story that signals the arrival of a new sublime literary talent from Cameroon. It is no wonder that her just published debut novel created a lot of buzz in literary circles around the world. It is definitely one book that I’m looking forward to reading in the near future.

Nkiacha Atemnkeng is a Cameroonian writer based in Douala, where he works for Swissport at the Douala Airport. His illustrated story book for children, “The Golden Baobab Tree” was published by Aalvent Books in 2014 and is available on Amazon. His work has also been published in the 2015 Caine Prize anthology, “Lusaka Punk and other stories”, the 2014 Writivism anthology, “Fire in the Night and other stories”, Fabafriq magazine, the Caine prize blog and munyori.org. His musings can be found on his award-winning blog, Writerphilic, nkiachaatemnkeng.blogspot.com and on twitter @nkiacha