Why does Akua Naru accept Africa’s music and spirituality, and neglect its people’s voice in her poems?

The 1997 film Love Jones features a scene in a dark jazz club at an open mic night where a young black man, Darius, performs an erotic spoken word poem dedicated to his love interest Nina. He references soul music lyrics: Meshell Ndegeocello’s “I’m digging you like an old soul record” in “I’m digging you like a grave”; and takes on celestial metaphors “Queen of 10,000 moons” and “distant yet rising star,” before ascending to the Yoruba orishas: “Is your name Yemoja? Ooh no. It’s got to be Oshun.”

This dizzying kaleidoscope of poetic images highlights the work of performers whose spoken word poetry combines a heavy sensuality with a mythical spirituality; works that tend to sexualize the male or female body while using it as an idol of worship; works that blur the lines between sexuality and worship. This duality seemed to characterize the struggle of an array of black performers of R&B music since the 1950s, who struggled to reconcile their gospel background with the sexual-energy of the music.

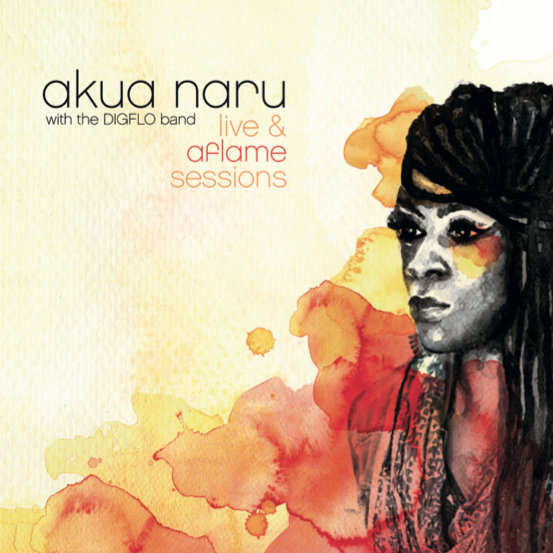

It is a duality that seeps through Akua Naru’s single “Poetry: How Does it Feel Now?” released on The Journey Aflame (2011) and on Live and Aflame Sessions (2012). The spoken word performance uses sexuality and worship in the same way Darius does in Love Jones to entice a male love interest; recited slowly with a jazz trio accompaniment. A jazz saxophone creates various ripples of sound that punctuate the reading, giving the impression of improvisation and a musical conversation between the voice and saxophone.

Unlike the tensions of R&B, the live jazz setting easily inhabits Naru’s double entendre of meanings. Her use of textual metaphors such as speech and writing, add a discursive aspect to the performance, turning lines of poetry into thoughts rather than kaleidoscopic images. Rather than plant flag posts to Yoruba gods, she gives a lover’s discourse in a meditative setting, attributed to the call and response structure of jazz.

Naru’s discursive powers are visible in the title of the song itself, a question, rather than a provocative answer: “I wonder, how does it feel to make love to your soulmate.” The matter-of-fact sounding question gives way to the kind of poetic responses that establish the songwriter’s thoughtfulness. “Kind of like writing poetry till climax,” she responds, “till the point and place where space and time match.” This juxtaposes love-making with the act of writing. The meeting of spirituality and sexuality is embodied in words which represent the body and the mind, and the act of writing as a symbolic unification of both.

However, it would seem that Yoruba mythology comes back to the center when Akua Naru takes on the Hip Hop persona— a character that differs significantly from her work as the meditative and discursive spoken word poet. Here, the performance of Hip Hop seems to draw out Naru’s anger, expressed through a stylized narration of the black experience in America. The spoken word poet makes explicit reference to Africa in “The Journey”, which becomes a target for her anger. In a complex narration, the allusion to Africa as origin of blackness is a double entendre of Africa as the origin of black suffering.

Beginning her journey with the history of blackness, “We were people on our land / African feet touch the sand,” Naru introduces the sense of origin as a physical relationship between American blacks and the African continent, narrated as black land. However, the intimacy of “African feet” touching the sand, creates a visual connection to the ocean, and therefore Naru roots her discussion of the origin of blackness at the ocean shores.

The Atlantic ocean, as the location of Black suffering is described here as “In the middle passage/ spoon fashioned, semen, blood, urine, dragging/ human organs splattered/ scattered across Caribbean.” She further describes “Somebody just jumped overboard cross the Atlantic/ skin branded/ left stranded.” By describing the horror of blacks aboard slave ships, Naru’s retelling of slavery justifies her anger towards Africa and its people. Episodes of departure are symbolized with the image of feet touching sand at slave houses and forts such as Elmina castle in present-day Ghana.

Already disillusioned with the space called Africa, in which the black subject is forced to depart by “a foreign man we never met” through slave houses on sandy beaches, Naru then seeks to emancipate the black subject through the political freedom chanting of “Free woman and man/ Stand tall.” One must question here, how could the black subject stand tall on the African continent if they were already enslaved and chained in the domain of savagery? Indeed, it is within this complex narration that one identifies the source of black suffering as located in Africa.

“The Journey” changes from departure to freedom. One wonders if Naru’s historical depiction of black origin does not imply that departure from Africa as the domain of black suffering is just one step towards black freedom. In this sense, slavery as the departure of black subjects to become emancipated within the Americas, is a narrative similar to colonialism as the moral vehicle through which, Africans on the continent become civilized, and that the black labor in the Americas is similar to the moral tools of colonization. These are what transform the black subject from savagery to humanity.

The discussion on African culture is treated separately from the savagery of African people. African music is humanized within this context, as if it came from a more mystical and metaphysical space, and not the domain of savages which is Africa. Therefore, Naru’s appropriation of “Conga djembe/ We sing a song for our first born” speaks of black music as originating in the communal rituals of African life.

In an exceptional reference of African spiritualisms, Naru uses the Yoruba mythology of Darius in his Poem for Nina in Love Jones. “We served God through a pantheon, then secular world came.” Here, one must pay attention to the poet’s Christian context. Akua Naru’s reading of the Yoruba orishas is convoluted precisely because it juxtaposes the orishas with the God of Christianity, placing them in his service. By purifying these gods through the school of the Greek temple, Naru once again distances another aspect of Africa from the continent itself. Yet in battle between time past and time future, Naru is disenchanted with American modernity’s secularism. Which spirituality is suited to the poet? It seems the tension of sexuality and worship resurfaces through the poet’s mismatched spirituality. To resolve the pain of the black experience, Naru prescribes writing poetry as love-making, African musical instruments, and the mythology of the Yoruba orishas, an approach appropriates African culture while negating the agency of Africa in the quest for black freedom. Even worse, this interpretation segregates African people while retaining their music and deities.

In this sense, in the poetic discourse of Akua Naru, there is a connection between Africa and slavery that renders Africa as the domain of black suffering in order to justify the pain of slavery. Why does Akua Naru accept Africa’s music and spirituality, and neglect its people’s voice in her poems?

Akua Naru’s Afro-pessimism that locates black suffering on the African coast differs significantly from Tupac Shakur’s poetic raps that locate black suffering on the American streets in the face of political institutions such as the prison system and the police that play the role of black oppression in America. And while it seems that poetry, which is equated to love, is the solution to black suffering, I point out the difference, here, between an intellectual and real approach to black suffering. In the song “Changes”, Tupac not only raps about the political institutions that cause black suffering “We ain’t ready for a Black president/ It ain’t a secret, don’t conceal the fact:/ The penitentiary’s packed, and it’s filled with blacks,” he also raps about instruments of change within the black community: “It takes skill to be real/ time to heal each other.” By preaching against “the way we treat each other”, Tupac points out the problem of intra-community racism. Through self-determined change within the black community itself, Tupac locates black freedom in America.

Critics have praised the film Love Jones for showing a positive image of black Americans on the movie screen. The film-maker’s use of poetry to symbolize the love between two black people is similar to Akua Naru’s suggestion that love is writing poetry and vice versa. As Intimacy and writing are prescribed for the literate black elite for whom Africa remains the origin of black suffering, Naru neglects the harsher realities of black life in America. What about the less advantaged blacks on American streets? What aspects of black life involve a constant cycle of daily violence? These are overshadowed in Akua Naru’s poetic discourse.