Dzekashu MacViban

As a latecomer to the Cameroonian musical scene, hip-hop has been on a gradual but steady rise in an over-congested milieu where, according to Kangsen Feka Wakai, “for at least two decades, it would play fifth fiddle to Soukous, Makossa (in all its apparitions), Bikutsi, and Bend-skin.” This change is due to a number of factors, some of which include: social media, music channels on cable, Nigeria’s Afropop boom and a “rediscovery” of the power of Pidgin English (creole) as the language of the masses.

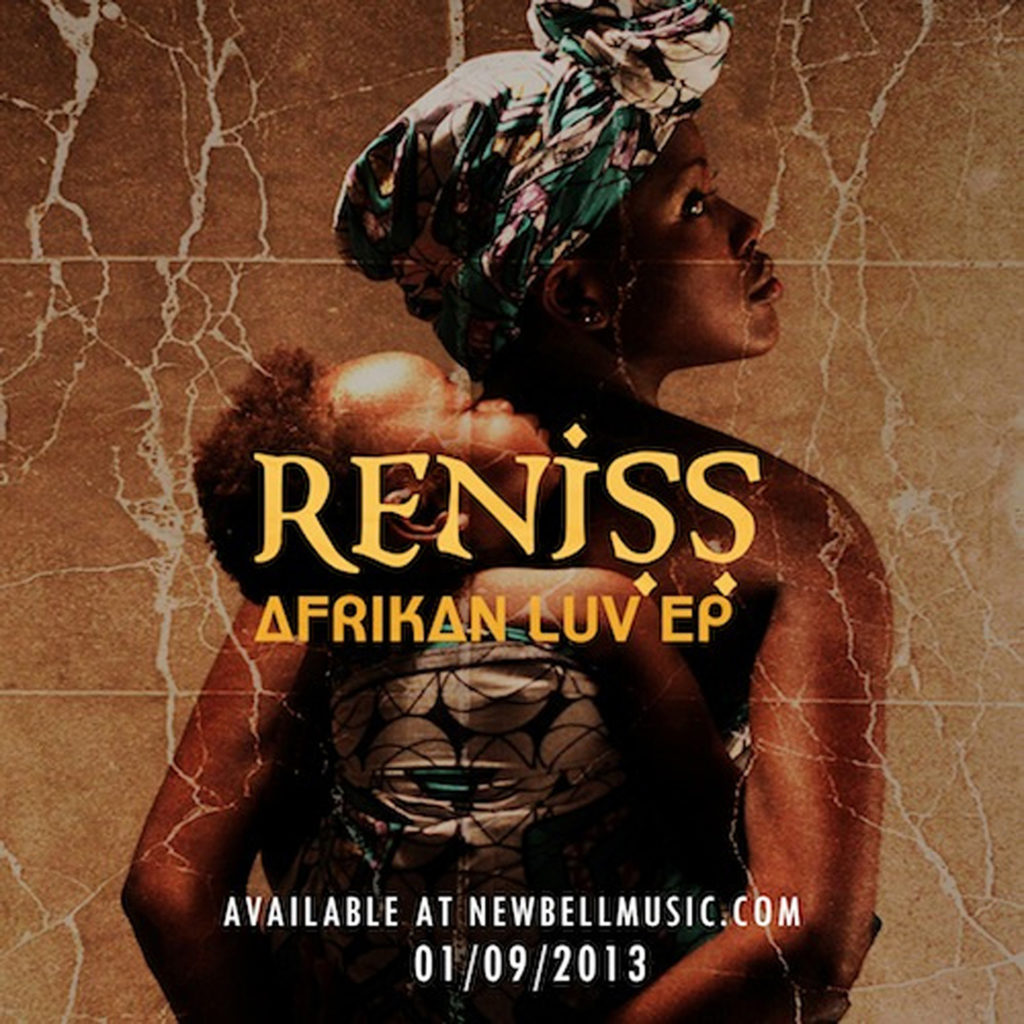

If there is one thing New Bell Music has secured for itself, it is the fact that it will go down in history as probably the most avant-gardist record label in Cameroon with its savvy handling of social media, experimental artists and deft emcee. New Bell Music is a record label founded by Jovi Le Monstre, erstwhile co-founder of the innovative label MuMak, and it represents artists such as Reniss, Jovi, Rachel Applewhite and Shey. New Bell Music’s first project is an explosive Afropop EP by singer and songwriter Reniss titled Afrikan Luv, released on September 1, which once more places Le Monstre as one of Cameroon’s most accomplished emcees.

The release of this album is a refreshing addition to the gospel genre in Cameroon, dominated by Nigerian songs which have flooded the market, producing copious lackluster offshoots which do a great disservice to our creative potential in this age of digital music where innumerable potential listeners are just a click away. Reniss has come a long way since the release of her first single “Fire”, which was met with a lot of enthusiasm on YouTube and today has about 9,325 views. “Fire” is the product of a confident young artist who is not afraid to experiment with music, and the result is a dexterous use of language which easily mixes and switches codes from English, Pidgin to Mankon, a feat which is evident early in the song when she says:

The people know I’m blest

Ma ting dem don di waka

Ma papa go gi mi swagga

Wuna di try ma patience…

Hot on the heels of “Fire”, and just as significant, however, was her second single, “Holy Wata” which is the kind of export-friendly song that could be played in a club and on a gospel radio station without any qualms, with its synthesizing of the mbira sound which has come to be known as Le Monstre’s trademark, and the video has about 16,000 hits on YouTube.

The first time I met Reniss was during Tito’s photography expo at the French Institute in Yaoundé, where she was in the company of her mentor Jovi, and February 16 (who is gradually becoming a household name in Cameroonian videography). She was radiant and spoke about her EP which wasn’t out then, and emphasized the fact that it was going to be free.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uO0qAaWL40U]

Afrikan Luv is an EP steeped in the Afropop genre and despite its innovative edge, it is “safe” music in that Afropop has come a long way from being marginal music. Afropop is a catch-all term encompassing the rich variety of contemporary African music styles, typically urban, electric dance music. Many have argued that Afropop is the heir to Afrobeat, a multi-instrumental genre incorporating traditional Yoruba music, jazz, highlife, funk, and chanted vocals, popularized by Fela Anikulapo Kuti in the early 70s, with an interplanetary impact whose influence can be felt in artists like Paul Simon, James Brown, John Coltrane, Frank Sinatra and Beyoncé.

In a piece from The New York Times, Jon Pareles opines that Fela is a figure to rival Bob Marley as both a musical innovator and a symbol of resistance, and Pareles further says that it is by virtue of his (Fela’s) relevance that a Broadway show dedicated to him was produced recently in the US (and much later in Nigeria) to make him accessible to the US mainstream music audience. The success of the show is evident when he says “The show has moved from a widely praised Off Broadway production, last year at 37 Arts, to the larger and more mainstream realm of the Broadway musical — from 299 seats to 1,050.”

Nevertheless, several music watchdogs have not wasted time in decrying the mediocrity of Afropop, which is mostly a hybrid genre with a lot of western influences, lamenting its comparison with Afrobeat and condemning as fallacious the claim the P-Square is the heir to Fela’s throne.

A host of artists collaborated on Reniss’ EP, from Jovi Le Monstre, who produced the album, to Sadrak and Krotal among others, and the ambitious nature of the album is seen right from the start, with the explosive title track “Afrikan Luv”, which shows that Reniss deserves to be mentioned by music critics in the company of Chidinma and Tiwa Savage because of her unique talent, and her performance during Flavour’s concert was just an apercu. The song combines African traditional rhythms and western beats in a unique paean.

The album explores love (not the immoral kind contemporary Bikutsi revels in, but rather a more sincere and unconditional one), faith, complication and on almost every level, it flaunts its Africanness— thematically, linguistically, synthetically and stylistically.

Track 3, “I’m Ready”, easily stands out in that it is the most R&B of all the sounds on the EP and one of the best songs. Its maturity is reminiscent of “Fire”, her debut single which showed her as a promising talent. The song is a meditation on faith and tribulations with a soothing melody that aptly matches its subject. While many inexperienced debut artists flaunt their novice status by trying too hard to be showy, the track shows Reniss’ voice as a natural voice which impresses without effort. In “The Apple”, Reniss’ voice croons a tale of temptation which draws on antediluvian themes and once more she comfortably switches language codes when she says:

Once you bite the apple

Na so ya eye di shine, you di see good and bad

Once you bite the apple,

You go know sey black no be white

Na so da ting di sweet for mop, and when you try you no go stop

Jovi’s verse on this track shows his ability to adapt to various musical genres and subjects, evident in his self-censorship on the track, as well as the whole album, and the absence of ego tripping ( a phenomenon which reappears twofold in Jovi’s latest single “B.A.S.T.A.R.D”, when Reniss sums up what he is saying in the following chorus: “Bastard kind chap inside bastard kind style/ Bastard kwa coco inside mbanga soup/ Jovi na bastard grand, inside bastard kwat/ Man na bastard fine chap inside bastard fine jap), but Jovi’s most memorable verse on Reniss’ album is on the track “LuV LOVE LauV” where his pidgin lyrics soar to impressive heights when he talks about hustling, saying:

Mola you wan die

Na pumu you wan see

Man whe yi go try

Na fo ground whe yi go sleep

Wu commot quartier na sika ngeme

Like you go kwata go ask ma reme

Wu be don decide fo remain kankwe

From Molyko right down to Mamfe

Pidgin English has always been popular in Cameroonian music and the post-independence popular culture pantheon is full of timeless songs whose notoriety reverbed in discotheques from Paris to Barranquilla. With musicians like Lapiro de Mbanga who composed and recorded what Index on Censorship has described as “a long list of biting texts on the socio-economic realities in his beleaguered country”, to Prince Nico Mbarga, whose song “Sweet Mother,” released in 1976 has sold more than 13 million copies, and Nneka’s remix of the song featured as a bonus track in her 2008 album No Longer At Ease. But the list barely ends there, because others such as Super Negro Bantous played a very “relaxed” highlife in pidgin (though they, like Wrinkers Experience [“Fuel for Your Love”] were mistaken to be Nigerian because they were based in Nigeria).

However, it is Lapiro de Mbanga who stands out because he used pidgin, a language the masses understand to express his political militancy and denounce the status quo as far back as 1985. Nevertheless, Lapiro doesn’t entirely sing in Pidgin. His approach to language in his music is a sort of linguistic pluralism and the mboko-pidgin he uses draws from several regional registers and street codes while his French flouts standardization. According to Peter Vakunta, Lapiro’s “diction remains in synchrony with the speech mannerisms and patterns of the people whose plight he bemoans.”

Not all circles valorize the unifying power pidgin has in Cameroon because pidgin has always been surrounded by controversy. In fact, the highest opposition to Pidgin comes from some members of the elite who look at it with contempt leading to its “quasi-criminalization”, a phenomenon which Dibussi Tande has decried in the following premise “the persistent attack on Pidgin English in Cameroon cannot be taken at face value because it points to a more insidious phenomenon, i.e., the steady destruction (deliberate or inadvertent) of Anglophone culture and identity.”

A lot of contemporary African musicians have gospel influences, whether or not they consider their brand of music as gospel. After almost losing their lives in a fatal car accident in December 2001, Mafikizolo, a Kwaito trio from South Africa, released an album based on how thankful they were to be saved by God titled Sibongile. Other African musicians who have in one way or the other been influenced by gospel include Goapele, Nneka, Lira, Swahili Nation and Maurice Kirya among others.

Reniss’ emergence is no accident. Afropop’s huge fan base in the generation of MTV Base has no limits, and the fact that her songs are meditative, party-friendly and danceable songs can only increase her visibility, which, when added to her talent and social media exposure creates a mélange that makes her EP a relish.