Cliquez ici pour lire en français

In “A Short History of Empathy”, Susan Lanzoni points out two interpretations of what empathy does. In the first instance, “empathy reduces stereotypical thinking; in the second, empathy as emotion-sharing draws too much attention to an individual, standing in the way of effective social change”. While there may be arguments for and against both stances, empathy, as a fluid prism through which divergent realities are perceived, means different things to people with different cultural backgrounds.

On its part, and by virtue of its inherent, self-conscious attempt to understand the human condition, creative writing is, more often than not, likely to create empathy as recent studies have shown. Nevertheless, such empathy can only go as far as readers who can read the language in which the creative writing manifests itself. This is where translation comes in. By recreating the essence of a work across languages, translation breaks linguistic barriers and gives us an insight into the lives of others, thereby unveiling realities and conditions—shared or otherwise—that have the potential to be factors of rapprochement rather than rupture.

It is against the backdrop of this premise that Bakwa, in collaboration with the University of Bristol, organised a creative writing workshop and a literary translation workshop in Cameroon in 2019. Based on creative writing’s capacity to create empathy, we seek to develop cross-linguistic empathy and sympathy amongst Cameroonians by translating stories and making them available in both English and French. The urgency of this endeavour cannot be overemphasised given the crisis currently rocking the country and stemming from issues of linguistic, cultural, and political identity and representation, or lack thereof.

Therefore, in June 2019, having been fortunate to receive funding from the United Kingdom’s Arts and Humanities Research Council to support this project, we started with two simultaneous creative writing workshops—one in English with five participants, led by Billy Kahora, and one in French with six participants, led by Edwige Dro. The participants came from all sorts of backgrounds and all parts of the country, but they all had something in common as younger Cameroonians and as aspiring writers. In each workshop, participants spent an intense week working together to learn about the craft of writing and the form of the short story. While our two workshop leaders had different teaching styles, both of them emphasised for their own group the ways in which reading, writing and living work together and how voices are forged through the act of literary creation. We ended the week with the third instalment of the Bakwa Reading Series.

After that week in June, we offered each participant mentorship with an established writer to polish their stories; Babila Mutia, Yewande Omotoso and Billy Kahora for the English-speaking writers, and Edwige Dro, Florian Ngimbis and Marcus Boni Teiga for the French-speaking writers. The mentorship process took three months and, through the dialogue and discussion built, mentees learned that effective writing is re-writing. Once the stories were finished, we were able to use these as the basis of a literary translation workshop, which took place over one week in October 2019. We also decided to include two additional stories: “Things the World Didn’t Tell You” and “Lifesavers”, culled from Bakwa’s forthcoming short story anthology, Of Passion and Ink.

Led by award-winning translators Ros Schwartz, Edwige Dro, and Georgina Collins, our fourteen participants spent long days learning about the specificities of literary translation as opposed to the technical or commercial texts they mainly encounter(ed) in their daily work or studies. They succeeded and enjoyed working collaboratively on prose, poetry, and dialogue/orality, at a slower pace and without tight deadlines, carefully mulling over words and phrases to find the most culturally and linguistically appropriate solutions.

One real highlight was a session where participants created Camfranglais versions of a passage from Jane Austen’s Emma. In another, participants chewed over how to (re)translate novels by Ferdinand Oyono and Max Lobe. Their critiques of UK English renderings of ‘bâtons de manioc’ and ‘sauce d’arachide’ (as ‘cassava sticks’ and ‘peanut sauce’, rather than more locally appropriate alternatives, such as ‘bobolo’ and ‘groundnut soup’) raised questions about who should translate Cameroonian literature and for whom, showing the need for extensive cultural knowledge, but also the challenge of finding and expressing the rhythms of a voice when translating literature. Each evening, we finished the day with a reading group session, which gave participants the opportunity to discuss literary translation theory and strategies, especially within an African and Cameroon-specific context. They also deliberated the role of the translator as creative writer and the acceptability of translator interventions—to what extent can/should a translator manipulate a text? There were many impassioned debates about the role of literary translation in Cameroonian society, language policy, and the feasibility of writing and translating texts into and out of local languages and dialects. These discussions had a direct impact on the work the participants produced. The week culminated in a Literary Translation Matters public conference at the Muna Foundation in Yaounde. This brought together members of the burgeoning literary translation network in Cameroon and gave some participants the opportunity to read extracts from their translations on a bigger stage.

Like the creative writers, the translators were also paired with mentors—Ros Schwartz, Georgina Collins and Roland Glasser for the French-English translators, and Edwige Dro, Mona de Pracontal and Sika Fakambi for the English-French translators—for three months of intensive work. During this period, they discussed many of their translation decisions at length, while slowly refining their writing over numerous drafts to produce a story that represents the source text but is a unique piece of literature in its own right, with its own poetic language. The result of all the above labour is the book in your hands.

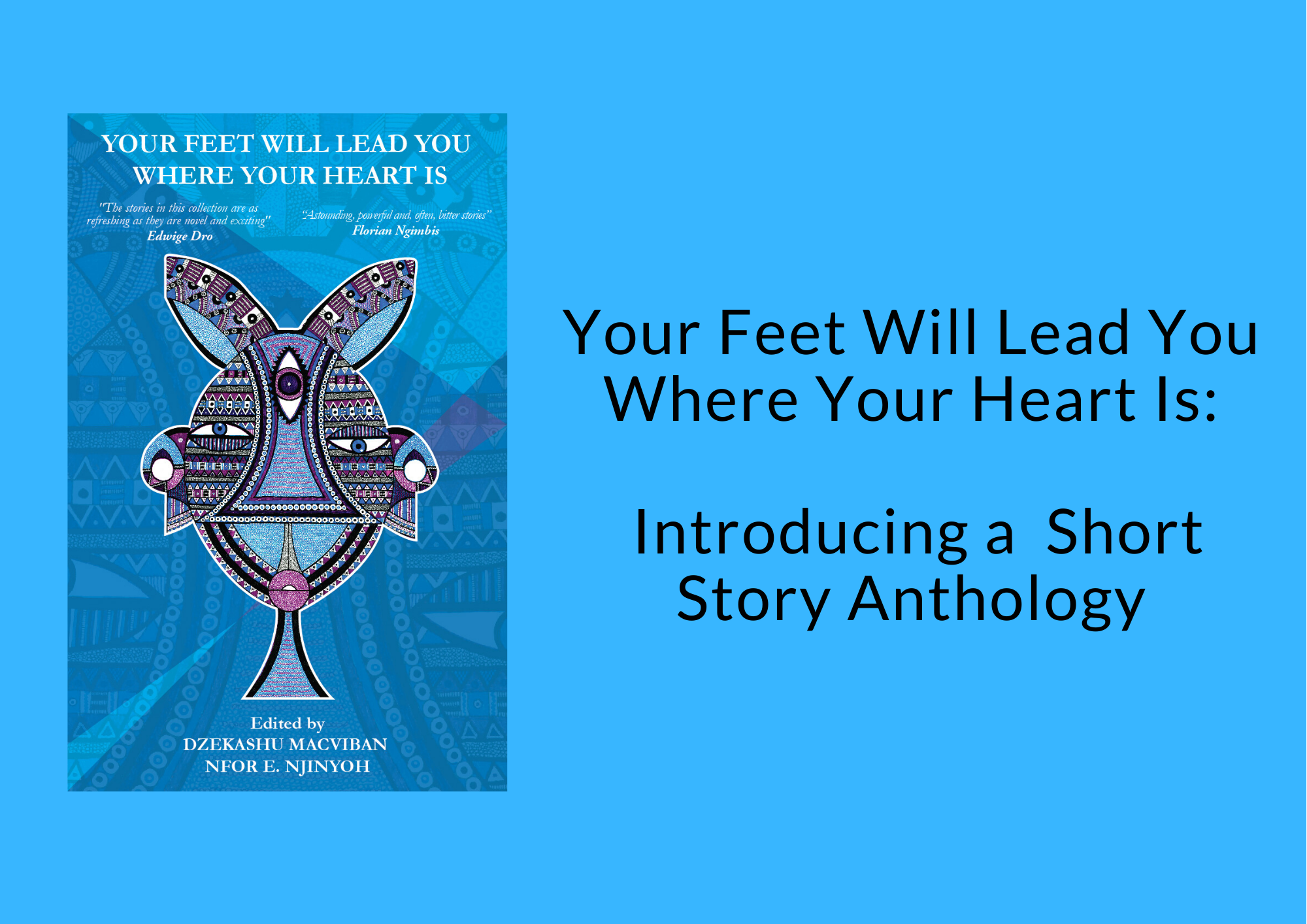

This project, which emerges partly from Dr Georgina Collins’ feasibility study, Literary Translation and Creative Writing Training in West Africa (2019)—that maps creative writing and literary translation networks in Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal—thus introduces a new generation of young Cameroonian writers and budding literary translators. This bilingual anthology highlights new directions in the Cameroonian short story, with stories moving from fantasy through existentialism and afrojujuism to realism. An unusual narrator in “Spittle Royale” walks the fine line between empathy, radicalisation, and primal instincts; in “Finding Jaman”, a correctional facility cleaner collects objects belonging to executed inmates, leading to an interesting discovery; in the eponymous story, siblings reconnect after forty years apart, unearthing secrets that will change their lives forever.

As a whole, these stories, through the prism of empathy, form a kaleidoscope of realities and experiences that, ultimately, portray us all as beings in quest of peace, love, and a sense of belonging. This, for us, is a drop in the ocean, a bottle thrown into these troubled seas, with the hope that someone else will get the message…

The Project Team

Click here to Order Your Feet Will Lead You Where Your Heart Is