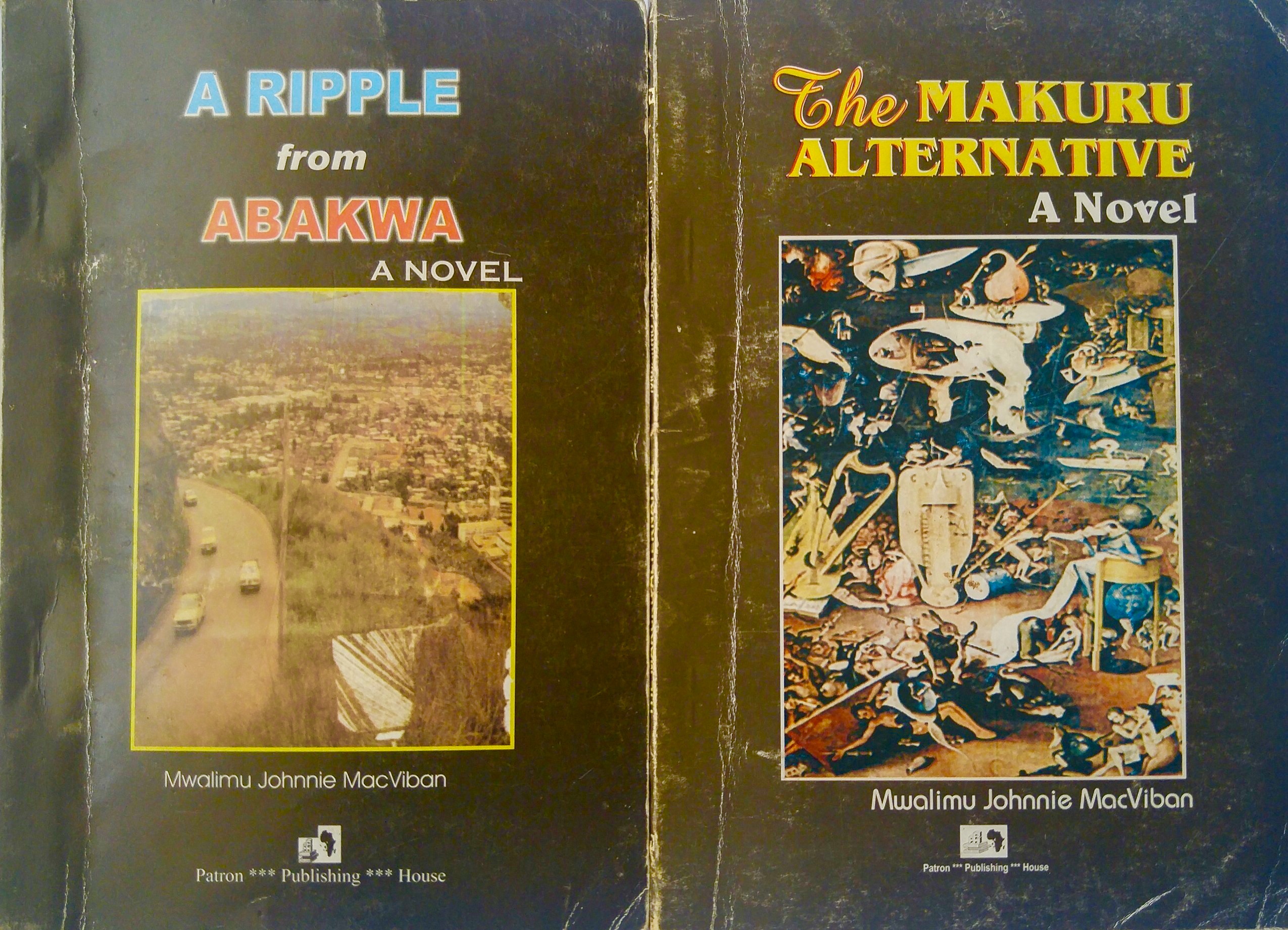

Mwalimu Johnnie MacViban is a household name in Cameroonian journalism and was featured in Index on Censorship in 1986 for an article titled ‘The Enemies of Democracy’. In 2011 he was shortlisted for the EduART Jane and Rufus Blanshard award for Fiction for his novel A Ripple from Abakwa. His other works include The Makuru Alternative, An Annecdoted Patchwork, The Mwalimu’s Reader and Twilight of Crooks.

Looking back at your career, what can you say about your time as a critic at Cameroon Tribune, and how is the cultural scene now, compared to the 80s when you worked with Cameroon Tribune?

Culture is said to be what remains when everything else has gone. Cameroon, culturally speaking, is very rich in its diversity. The cultural scene then was groping in the dark because of many restrictions and self-censorship. Today, we are in a new dawn with the coming of democracy and its attendant freedoms. Many cultural facets are now out of the self-imposed cocoons and are standing tall to meet today’s challenges. Writers today can speak out and stretch their imaginations to the limit. New writers now question their time— the here and now, what we have done with ourselves and governments after independence. But writers find themselves in a fix. Globalization and mass media have created a decline of attention and writers are pouring out creative fiction for a public that takes reading as a last resort.

In your first two novels, The Makuru Alternative, and A Ripple from Abakwa, there is no nemesis or antagonist in the conventional sense of the term. In The Makuru Alternative, the government or the powers-that-be can be considered as the nemesis, but in A Ripple from Abakwa, it is more complicated. Why this fascination with the need to annihilate the nemesis?

It is true that the traditional novel has a protagonist and nemesis. Political fiction has always been popular because Africans have suffered from their own governments. The writer will always pick on a fictional government to lay bare his point. Truth and good governance are very elusive concepts here. So for a novel like The Makuru Alternative to handle a political theme that centers on one honest man against a system of enshrined kleptocracy seems fascinating. The powers-that-be, political thuggery and electoral fraud are the themes that committed political writers embrace, asking the too obvious question— which way forward.

There is a sentence in Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf which adroitly describes the protagonists of your first two novels: “I saw that Haller was a genius of suffering and that in the meaning of many sayings of Nietzsche, he had created within himself an ingenious, a boundless and frightful capacity for pain.” Was your construction of Dr. Sullivan Embale and Leslie Shuffon conscious of the fact that they were alienated from society and ‘geniuses of suffering’?

The core of the matter is that of soul-searching in a political system that has willed itself on the people. In the two novels, the chief characters are conscious that the system is bad, but all is not lost. They undergo the sufferings in the name of others. It is a kind of purgatory or catharsis. Some people are weak and will succumb to dictatorships. But there is that voice crying out in the wilderness— isn’t there one man to help save the situation. This is the kind of thing that gives credence and realism to the struggle of African nationalists like Nkwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, and Thomas Sankara. The daring aspect is uplifting.

The Makuru Alternative, which is your maiden novel, stands out as a fragmentary poetic novel laden with intertextuality, introspection and allusions which range from cinema to cultural theory, given that the novel is steeped in postmodernism. What writers have had an influence on your style?

When I wrote The Makuru Alternative, I saw the poetic picture standing before me. The story is multi-layered and challenges readers to decipher it. The story is also written with the screen in mind. Many writers have influenced my writing style and I’m indebted to that literary background. Some of these writers include: Nadine Godimer, Tom Wolfe, Woody Allen and Henrick Boël, whose catch phrase “we writers are born interferers” is always ticking in my mind.

Your novels expose dictatorial abuses of power, yet, of the various forms of subversion that exist in your books, the one you describe at length is the Russian-styled samizdat, wherein texts are clandestinely printed and distributed. Do you think this system practical and does it fly under the radar?

Since independence in the 1960s, African countries have been known to be the bedrock of dictatorial abuses of power. We can’t just write the epoch off, we must talk about it in all forms of fiction and journalism because African history books don’t have the story of what really happened. If we writers shy away, we are equally guilty of their crimes. Take a roll call of the bad and the ugly rulers Africa has had— Sekou Touré, Idi Amin, Mobutu Sese Sekou, Jean-Badel Bokassa and Sani Abacha. Writers need to remind people that literature has no taboo subject.

In A Ripple from Abakwa, you bemoan a near-mythical past, now lost, which centers on the formative years of Abakwa, in the way Salman Rushdie laments the changes in Kashmir in his novel Shalimar the Clown, and in an interview with The Paris Review, Rushdie says it “was a kind of attempt to write a Kashmiri Paradise Lost.” Is your near-mythical description of the past faction, or pure fiction?

You have rightly said it. A Ripple from Abakwa is faction, which is fiction spiced with actual happenings. Every writer has a place of birth and nurturing which fascinates him. The writer goes on to mythologize this place for self-satisfaction, but with many changes taking place, one bemoans a time long gone that cannot be relived. The writer longs to be back there, turning back the hands of time in a nostalgic adventure of fiction. This is where fiction is stronger than history, but both remain complimentary.

The language in both novels is very self-conscious, with a penchant for neologisms, word play, code switching and mixing. As it is wont to happen with writers who choose this path, complaints of inaccessibility are never absent. What has it been in your case?

No novel is ever easy to read. Some of the complaints of self-consciousness in my novels may be true. If the author is not himself, how does he go on then to write? The first law in writing is that the author has to know himself so as to know others. He is like a juggler with four apples doing the difficult task of containing gravity. Readers ought to observe the rules of fiction— read a work as it is written, not as they think it ought to be written. No book is ever difficult to read because perseverance opens the door to decode layers of meaning. A writer therefore uses wordplay and expects to achieve an effect.

Politics stands out as a major preoccupation in your fiction, and despite the fact that in A Ripple from Abakwa, Leslie Shuffon’s search for a paramour is shown at great length, the novel remains a political novel. Why political novels?

I think that as I have earlier said, politics is super factor that surrounds us. In Africa today, the government is everywhere; it is like Big Brother and writers can’t be insensitive to the overbearing factor of politics. After all, it is said that man is a political being. Our politicians are very suspicious of writers, thus the writer-politician divide that seems to be ever widening. Whatever happens, writers shall always be, despite persecutions. New African writers stand in the footsteps of their predecessors and face new challenges.

Very interesting interview! Relevant and highly accurate!

A writer has to connected to the world, to be credible and positive in his writing.

“Read a work as it is written…” That’s what has to be, provided the author has written something to be read.

Globally, I enjoy the words of Johnnie MacViban. Now I hope to read his novels and experience the labourer under the burning sun.