Catherine Gilbert

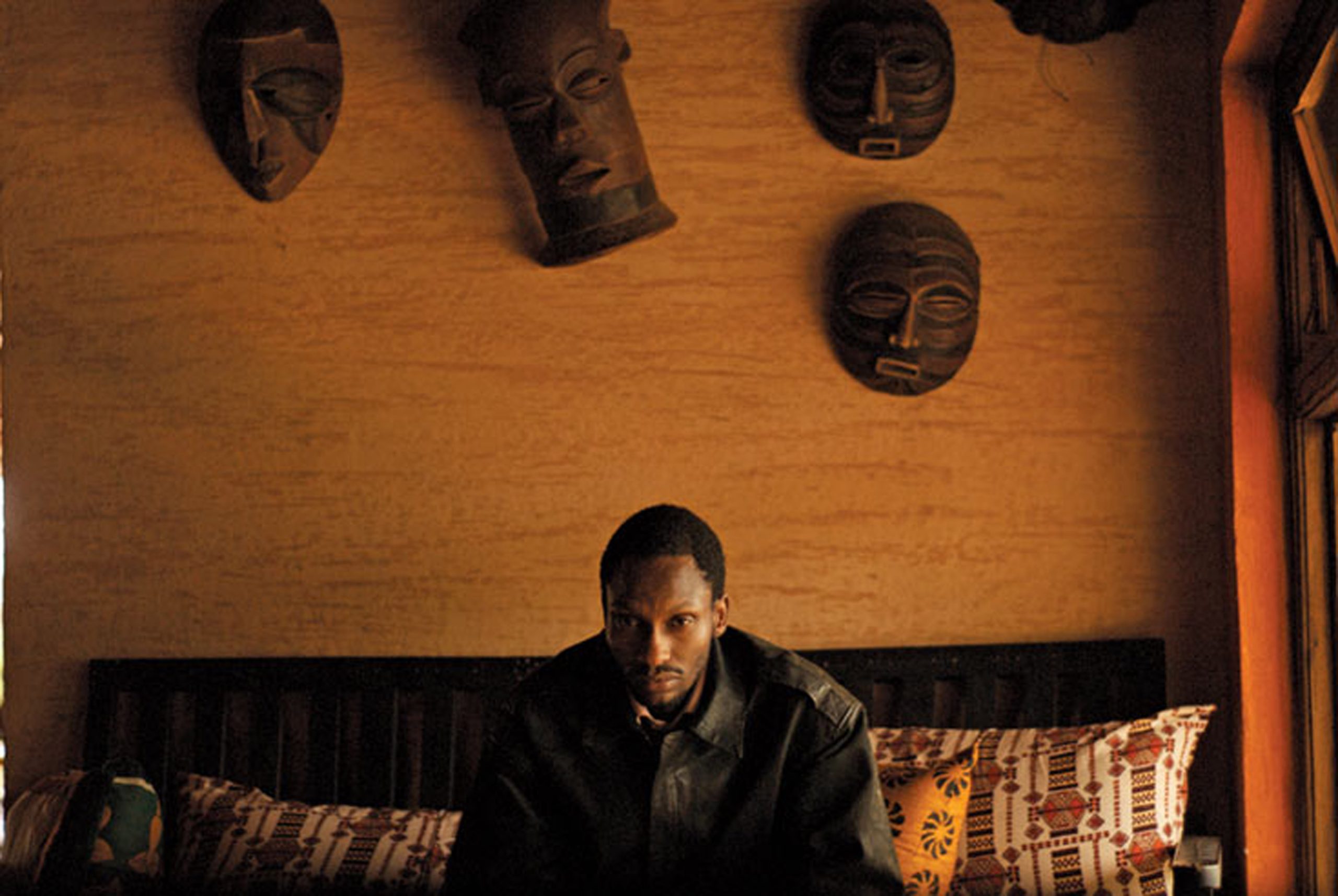

Matière grise (Grey Matter), 2011. Directed by Kivu Ruhorahoza. 110 min. Kinyarwanda and French with English subtitles.

Originally published on Africa in Words

2014 marks the twentieth anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda in which as many as one million people were systematically slaughtered in a period of just one hundred days. Recent years have seen a growing number of artistic responses to the horrors of 1994, spanning literature, film, art, photography and theatre. A recent example is the exhibition ‘Rwanda in Photographs: Death Then, Life Now’, held earlier this year at London’s Inigo Rooms, curated by Zoe Norridge and Mark Sealy. The ever-increasing filmography includes award-winning films by foreign directors, such as Lee Isaac Chung’s Munyurangabo (2007) – the first narrative feature film in the Kinyarwanda language – and Alrick Brown’s Kinyarwanda (2011). One response that is too often overlooked is Rwandan director Kivu Ruhorahoza’s Matière grise (Grey Matter), the director’s first feature-length film released in 2011.

Set in Rwanda’s capital Kigali, this film-within-a-film follows determined young film-maker Balthazar’s (Hervé Kimenyi) attempts to direct his first project, The Cycle of the Cockroach. The story highlights the continued difficulties surrounding artistic exploration of such an extreme traumatic event, not least when the authorities refuse to fund Balthazar’s film, telling him that the story he seeks to portray is simply ‘irrelevant’. The commissioner (Jean Pierre Kalonda) Balthazar meets with advises him instead to make a film about contemporary social issues, such as gender-based violence or HIV, but Balthazar sees their narrow-minded attitude as precisely part of the cycle of violence that he wishes to denounce. Refusing to give in to their demands, he resolves to make the film on his own, seeking financial assistance (unsuccessfully) from a loan shark and the support of his actors and friends. Balthazar’s experiences echo Ruhorahoza’s own struggles in making Matière grise.

We are exposed to Balthazar’s deeply personal vision for his film as he forcefully expounds his ideas to a friend over the telephone late at night, and as he rehearses scenes for the film with his actors. As Balthazar lies on his bed, unable to sleep, imagining the voice of a radio presenter calmly intoning the message of genocidal hatred, the scene shifts to a former perpetrator (Jp Uwayezu) lying on his bed in a mental asylum: Act One of the Cycle of the Cockroach. We watch as the ‘fou’ (crazy man) hunts a cockroach in his room, interspersed with glimpses of his memory of hunting human cockroaches in the fields (the perpetrators of the genocide dehumanised the Tutsi by referring to them as cockroaches during the genocide). The director Ruhorahoza/Balthazar even goes so far as to depict him raping his captive.

Balthazar’s film then seems to become reality in Act Two as we are drawn into the lives of Justine and Yvan (Ruth Nirere and Ramadhan Bizimana), a brother and sister whose troubled relationship brings out the complexities of the hardships endured during the genocide and the lingering effects of trauma. Yvan has recurring visions of his parents burning, visions that are more real to him than the present moment, and refuses to remove the protective motorcycle helmet from his head. The visual impact of Yvan’s visions on the viewer make it difficult for us to distinguish between what is real and what is imagined, although we later discover that Yvan did not witness these scenes himself. When Yvan claims he wears the helmet because he was cut with a machete, his sister contradicts him saying, ‘You don’t have any scars. They didn’t do anything to you. You weren’t even here during the war’. Actor Ramadhan Bizimana won best actor at the 10th Tribeca Film Festival in 2011 for his portrayal of Yvan in this film.

The intimate camera work portrays the breakdown of communication between the two and, in turn, Justine’s frustration as she tries to bring Yvan out of himself and take care of him. Close-up shots of Justine smoking alone in her room heighten the growing sense of isolation she feels. Forced to act as Yvan’s parent and guardian, she even has to perform sexual acts with a psychiatrist (Juma Moses Nzabandora) to ensure her brother receives the treatment he needs. In this manner, the film sensitively explores a range of questions relating to secondary trauma, the difficulties survivors continue to encounter in getting the care they need, and the often debilitating effects of the genocide on the individual imagination.

The film culminates with the exhumation of their parents’ bodies, where the image of a hoe plunging into the earth is replaced with a machete hacking down. Shortly after this we see Justine in the asylum watching a cockroach, which runs under the door to be captured by the ‘fou’ in a neighbouring room, thus bringing the film full circle. Matière grise provides viewers with glimpses into the brutal violence of the genocide and the ways in which this violence continues to haunt the present, leading the viewer to question whether the protagonists can ever escape the cycle.

According to the director, the film is ‘a story about the capacity of the brain to create, destroy and auto-destroy’. Ruhorahoza’s stark depiction of the blurring of what is real and imagined, through the damaged psyches of his characters, provides a nuanced and in-depth exploration of the complex realities of a society that is still trying to rebuild itself in the aftermath of genocide. A slow-paced, cleverly-constructed film with a minimal cast and soundtrack, Matière grise allows viewers plenty of time to absorb the full extent of the protagonists’ seemingly futile mental and physical struggles. This film will haunt viewers long after the closing credits.

Catherine Gilbert is currently a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Department of French and Francophone Studies at the University of Nottingham, working on the AHRC-funded project ‘Building Images: Exploring 21st century Sino-African dynamics through cultural exchange and translation’. Her research interests span Francophone African literatures and cultures, literary translation, life writing and testimony.

Unfortunately, the film is not available in my country, so the review will do for now in a world for which “globalization” means that we buy the same international brands but are unable of sharing art, what really matters.