Petit Pays owned the nineties. And if he didn’t own the entire decade, then he owned the most significant part of it. And if he didn’t own the airwaves, he certainly owned sidewalk speakers and dance floors. The ‘matinee’ generation would come of age dancing to the sounds of ‘Nioxxer’, ‘Maria’ and ‘Polissy’.

If Lapiro de Mbanga stormed through the gates of censorship in Cameroonian popular music in the mid-eighties with his abrasive diatribes against the socio-political order, then Petit Pays widened those walls with lyrics that were at once irreverent and suggestive. His were songs that were layered with innuendos, social commentary and were meant to provoke.

If Lapiro was the revolutionary, Petit Pays was the provocateur. If Lapiro got the masses dancing, thinking and angry, Petit Pays wanted them dancing, laughing, thinking and redefining their perceptions.

When trends in Cameroonian popular culture are eventually chronicled with the clarity of hindsight, Petit Pays—Lapiro de Mbanga notwithstanding—will no doubt emerge as perhaps the most influential singer of that era.

Having emerged out of the dregs of the golden era of Makossa, a genre that had dominated the Cameroonian music scene since independence—a sound born in the native quarters of Douala, Petit Pays will commandeer this ‘new’ Makossa sound across the continent all the way to pockets of African immigrant communities across the Atlantic.

Francis Nyamnjoh and Jude Fokwang have convincingly argued in their study of ‘Politics and Music in Cameroon’ that Makossa’s prominence in the local musical sphere was a consequence of both geography and history.

“Douala’s strategic position as a seaport and Cameroon’s largest commercial center gave Makossa an early lead. The fact that this brand of music was more easily electrified was an added advantage to its rapid development and modernization. Its gentle, bourgeois, cosmopolitan and adaptable rhythms and dance styles made Makossa the perfect music for urban Cameroon at a time when expectations of modernity were highest,” the authors suggest.

But, Petit Pays’s sound was a hybridized version that incorporated elements of Zouk and Soukous without straying too far away from its Makossa roots.

Makossa, in essence, had always been a gentleman’s affair. Makossa was Nkoti Francois in a four-piece suit, Moni Bile in a bowtie, and the avant-garde tastes of a Dina Bell. However, Petit Pays’s sound, and eventually his image, was radically different from the unadulterated ‘old sound’ championed by the likes of purists like Toto Guillaume and Ben Decca.

It was a sound that did not confine itself to the heartbreaks, crooning, ‘bal a terre’ and relationship confessionals that had come to lyrically define the genre. It was not the youthful and soulful sound of Epee et Koum; Petit Pays crooned too, but did it while subverting decorum and offering social commentary, and unlike the gentlemen of the seventies—the Makossa nostalgists favorite epoch, he courted controversy. And controversy sells.

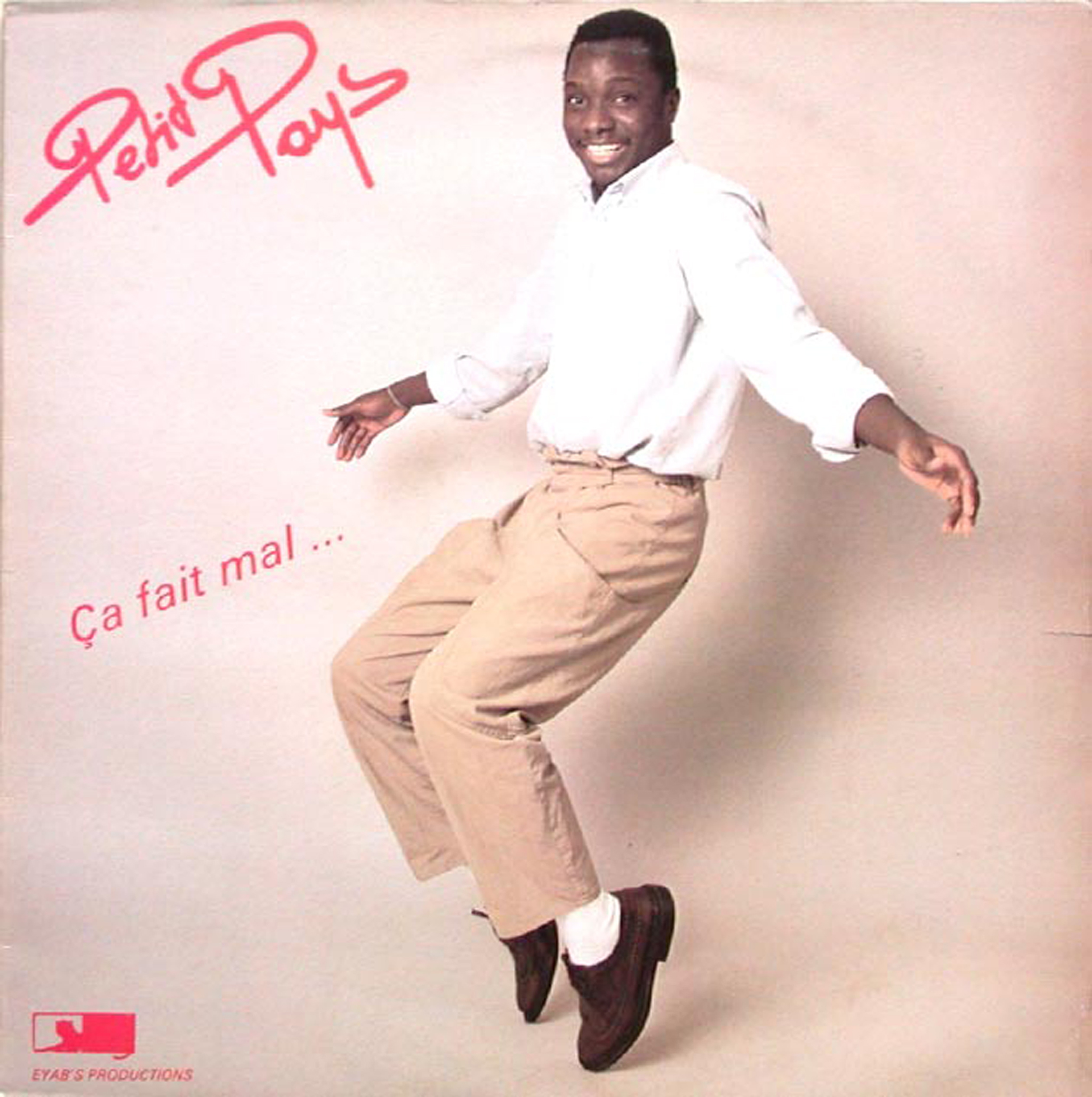

His apparition [without controversy] on the musical landscape would occur in 1987 with the Eyabe Kwedi produced ‘Hausa’. In the autobiographical title track he would introduce himself as the son of an Hausa father and a Douala mother. This album, and subsequent albums by this detribalized son of Makepe would even elicit hope amongst Makossa enthusiasts in need of a messiah to counter the sonic assaults coming from neighboring Yaounde [Bikutsi] and as far away as Kinshasa [Soukous].

But it was the release of his opus, 1996’s ClasseF/M that would establish him as an icon and immovable boulder in the pop-cultural landscape. The album came in two tapes, Classe M and

Classe F.

But, it was the cover of Classe F, which made headlines and kept flippant tongues busy—posing, like a minute old baby—think of biblical Adam before self-awareness—his hands covering his crotch, mischief all over his face.

It was an image that rattled and startled the gallery of official and unofficial censors. It was as if he was saying “je m’en fout!” But this act also seemed like a metaphorical meditation on the polity’s collective nakedness after the embers of liberation had died following the political euphoria of the early nineties. It was a rebuke at the parochial and hypocritical. It was Felaesque in its audaciousnes, jaw-dropping and shocking. But above all, it sold 50,000 copies in a week—a record, and made him an icon.

In fact, before Petit Pays could even claim fans in places as far away as Abidjan, Ivory Coast, he had imagined himself an icon. He had enthroned himself the King of Makossa Love. He had even declared himself ‘l’advoacat defenseurs des femmes’ even as he objectified those same ‘femmes‘ in his lyrics. He would claim to be ‘number one Africa!’ He became Le Turbo! And like other legends of sound and verse sang of his death as if to remind listeners—and himself—that he was destined to be great.

Today Petit Pays lives on Rue Petit Pays in the Makepe neighborhood of Douala in a mansion inscribed with his aliases: OMEGA and TURBO.

According to most published reports, he was born in that neighborhood on June 5th of 1969. In his late teens, he would leave for France to study law, and according to legend was repatriated. It is even rumored that his band, Les Sans Visas, owe their name to that experience.

In any case, his decision to bare it all still stands amongst his most timely and daring artistic statements. With that act, he transformed the musical landscape from sheer entertainment stage and dancefest into a living canvass of socio-political expression. The image uttered an ocean of words. But it was the music that reminded those who might soon forget that, “meme les chef d’etats meurent”.

So, when he sang of ‘Polissy beat ma back oh…soldier e beat ma back oh’, it was a mere regurgitation of scenes scripted on the streets of Kumba, Bamenda, Bafoussam and Douala. These songs and others reflected an engaged and conscious artist.

In a way, and in the context of the time, Petit Pays’s decision to bare it all could even be viewed as an act of self-sacrifice, a mutilation of mores, and an altering of perceptions and an artistic risk. But as fate would have it, Classe F/M was not just an attention-grabbing gimmick. It was a meticulously executed project that varied in mood that can even be credited for helping usher in the short-lived Makossa subgenre, Zengue. But ClasseF/M would also be his last great album.

In recent years, Petit Pays has graced an album cover in drag, baptized people in his name, given himself countless aliases, kept concert goers waiting for hours, rambled through songs, shot awful videos and made many sloppy albums.

He had always sang with a hoarse, at times off-note key, but could count on stellar production for the accentuation of his sound. His true gift was always the persona that came with the singer: a sharp wit and keen eye for the ironic. He was an average songwriter with a knack for catchy choruses and hooks, but it was his understanding of the role of marketing and the power of the artist in society that might have been his greatest talent.

These days, the music Petit Pays makes sounds like bad samples of his earlier releases. The crisp production of his heyday has been substituted by a crude production. The social commentary and iconoclasm have now taken a backseat to creative monotony. His recent releases have been at best lackluster. It is as though he doesn’t even try. As the social and sonic flame he helped spark fades in the dusk of our collective consciousness, one is left to wonder: does this King still rule supreme or has he lingered to the domain of comfort-induced apathy?

Kangsen Feka Wakai is the author of Asphalt Effect and Fragmented Melodies. He is also the Founding Editor of Palapala Magazine. He lives in Boston, Massachusetts. You can read an interview with him here .

Great write-up, I am regular visitor of one’s website, maintain up the nice operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

As a Group working in the African music industry “Music from Cameroon Kassa World Music the Music Travel” is of great interest to us

well written thank you 🙂

http://www.africanmusic24.com

Nice post. I used to be checking constantly this weblog and I am impressed! Extremely useful information specially the closing section 🙂 I maintain such info a lot. I was looking for this certain info for a very long time. Thank you and best of luck.

Nice post. Thanks.

As soon as I noticed this site I went on reddit to share some of the love with them.

Wow! Beautifully written and so on point. I think Petit Pays Should read this!