Wirndzerem G. Barfee

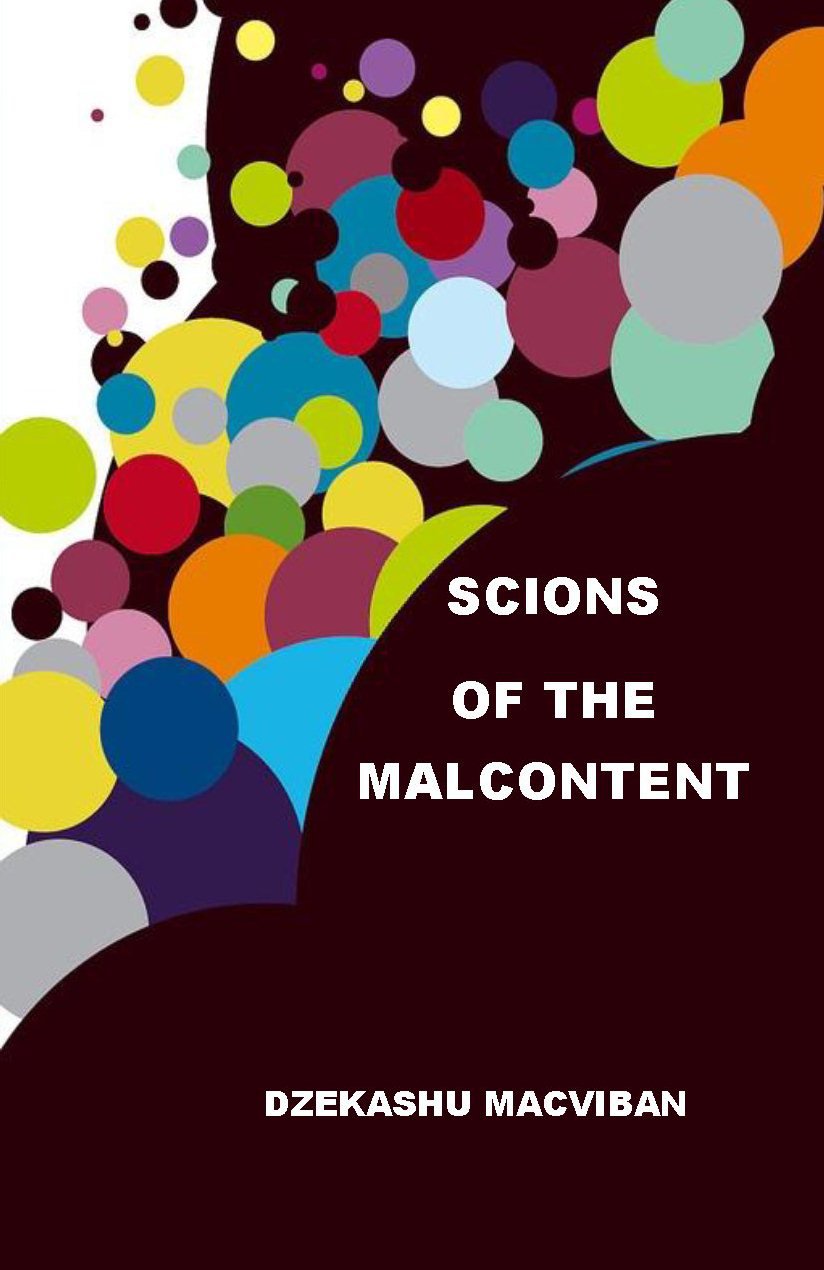

A work of art is, and can be, read from multiple perspectives. One of the most engaging perspectives to read Macviban’s collection, Scions of the Malcontent (SOTM), is by collapsing the opposition between the verbal and graphic articulations, and as such creating a complimentary dynamics that participates in the integrative reading of the text. From that prism, it is clear that you may not delve into Macviban’s poetry collection with an indifference towards the aesthetic and semantic impression left on the sensitive reader by the relationship that rivets the title to the front-page graphic art. Because this will, in less assuming ways, govern the exploration of those subsequently enfolded by the cover pages.

Now that we know the christened title, SOTM, published by Miraclaire Publishing, let’s try to see how the preliminary substance and style germinate from that seed. ‘Scions’, referring to the progeny or offspring of the disgruntled, incites a generational nexus or condition: the siring generation is located and colored in a zone of discontent with the reader interestingly left to speculate and define eventually the psychic composition of the resultant generation. The title’s focus is on these scions, the off-springs of the discontented lend greater import and weight to the interpretative inclination towards analyzing the complex of the said offspring in reaction to the parental discontentment. How are they going to handle the condition of restlessness, dissatisfaction, frustration and of the grouching and grousing bequeathed unto them by their so characterized progenitors? That is the baiting interrogation we approach the collection with while still contemplating the title.

And now that we have dismembered some of the pertinent elements encased in and conveyed by the title, let’s then go out there, me and you, into the streets and pick up the book and study its cover graphics to see how they tie with title’s content and style. Picture. From the base of the front page and rising up, rightwards, we are presented a dumpling, protuberant landscape colored in lugubrious pitch-black, and lent the bulging silhouette of a naked pregnant woman, sitting, and framed from tummy down to the thighs, and no more. Is she the dark metaphor for the truncated, disgruntled, discontented parturitative generation? Curieux lecteur, let’s dissect and sample on. From the interstice of the expectant woman’s dark thighs, a motley maternity of variegated bubbles or balloons amply sprout and rise up into a black and white sky.

What does this choir of multi-colored floating objects convey as metaphoric answers to the erstwhile baiting interrogation related to the title? Is the sinister condition of the progenitors begetting and inspiring the colored and rising hope of, and in, the scions through the prism of these ballooning prospects? Or are these prospects simply shimmering mirages of colored bubbles that will be burst, to spill the mere air of their vain substance, before they touch the sky? Why is the sky a low, stifling, black and white sky? Or is it the “pitch black night, colored by sparks” that the poet himself authors in “Troubled Dawn” (p.12)? So, now that the questions have been cast on the mat of tellers, what dibia, what marabout, what ngambe-man, what Madame Sosostris and what clairvoyant will say the sooth out of this crystal ball?

We will now open the book and explore to question again, and find out the truth of the matter and the manner.

SPEAKING OF THE MATTER.

The substantial at this juncture explores the thematic concerns as they relate to the dark belly and psyche of the siring and locate that thematic in juxtaposition and connection with the enigmatic and ambivalent symbolism of the tinted balloon/bubble conundrum. In this line we shall seek to address the content of discontentment and the content of contentment in order to unravel a third position of the ambivalence immanent in the fate of the scions. This reveals a simplified schematic dynamic that moves from the dark discontentment of the earlier generation of sires to the hopeful contentment of the scions and finally to the ambiguity of trans-generational contentment and discontentment.

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1zhfcx_dzekashu-macviban-a-woman-of-the-people_music

Content of Discontentment

Here we bundle themes in the collection whose substance is hinged on the indictive and negative issues, such as, but not limited to, bad politics as characterized by endemic dictatorships, mal-governance and strife; societal decadence typified by moral bankruptcy, violence, corruption, deceit, cheating and sexual deviance; the horrific or the macabre, epitomized by occultism, ritualism and bloodletting; the sense of loss embodied in issues of death, departures and lost values. But we will only sample a couple of themes from some representative pieces.

In the arc of these sinister poems, we have representative poems, appearing in the condignly titled subsection, All is Turmoil, such as “Comfortless Memories”, “Seasons with the Sun” and “What He Does Best” that particularly engage discontentment towards, and indictment of, ambient tyranny. In “What He Does Best”, the despots “With a presence [in them]/ [They] persecute/Others filled with a lesser presence” and there is no “room for the righteous” because here the malcontented citizens are dealing with sanguinary ogres who drink from fountains of blood, take up their heads and their “lips are scarlet” (p.25). This image presages that of the Togolese dictator, Eyadema in “Comfortless Memories” whose rule the poet writes to indict and on the tyrant’s death, persona mocks:

Tyrants and sycophants sit with comfortless memories

Perturbed by past, illegal and gory glories

Their future reserves nothing but gloom

………………………

When the wheel turns many a great fall. (SOTM, p.27)

“Seasons with the Sun” picks up the tyrannical theme and specifies a generational disgruntlement and helplessness, in “an enriched bitterness” of old. This condition is rendered tragic by the perpetual cycle of despotism where one tyrant replaces the other and where the dry “seasons with the sun” remain an excruciating and scalding monotony that holds the dream hostage in a standstill position:

Of old had stood the dream

As with enriched bitterness

We sought with change, the gleam –

But a change of tyrants little profits our distress.

……………………………

…………………………..

The seasons are the same in the wilderness –

Seasons with the sun. (p. 29)

The hope in the future generation lies in the meteorological, or rather climatic, metaphor stating that “Only rain can change the wilderness!” of tyrants and their unproductive and oppressive dry seasons. The direct and implied conclusions here are respectively that only a change of seasons and, by extrapolation, a change of generations, to that of the scions, can bring hope of freedom and bliss.

“Much Ado about Bakassi” (p.21) and the long piece “Fragments” (pp. 31-40) are poetic pieces teeming with strife. The Bakassi poem mourn the fallen, who stagger and fall into sludge and blood. They fall cut down by “deafening hellish gunshots” and their dead dreams now turned to dust by wars “unsagely waged” when a roundtable would have done the deal to keep the ghosts of the soldiers at bay. That is the poet’s wise counsel to the scions having learnt from the past condition of their warring malcontents. “Fragments” rolls off with a “land plunged in war”:

Now the troubled land shook earth-hall and all

On combat bent, to strike one stroke

……………….

And the shouts were rude intrusion into the day’s bliss. (p.31)

Furthering the poem to the Fragment II with the terrible “army arrayed for battle”, the poet poignantly observes and rhetorically asks: “the calamity rain during this period of bane rests unmatched/What greater transgression can we entertain?” (p.32), as Part III choruses echoes of T.S. Eliot’s “Wasteland” that:

April was the cruelest month, yes

It bred a gathering human storm.

With meteor shower like heavy rain on flowers

The forces opened fire…on the gunless.

The air seemed alive with bullets as they tore the tensed air (p.33)

Depicting the aspects of societal decadence, the poet vectors this home through poems like the “Mendicant of Yeruwa”, “Princess of Thieves” and “Woman of the People”, amongst others. In the mendicant poem the vicious putchist-turned-beggar, presents us with a situation of extreme moral bankruptcy where praise-singers will sing your praises or atalakus – on existing merit, the exaggerated merit and even the inexistent merit – in order to have their farotage. Once the said rewards for the sycophancy are not forthcoming, the mean breed of griots will spit venom with a “forked tongue” on your person and name as a stingy, crafty creature:

Out of the depth of a threadbare bag

An ever empty bowl, beseeching.

The seed has been sown

A positive move plunges him into reveries

Of his troubled dawn

Punctuated by showers of Allah’s benediction

The contrary unleashes his forked tongue

Which slices the air, the heart too (p.22)

The poet operates an agency of animal images that reinforce the uncivil degeneracy of the mendicant and his likes by putting into play the serpentine symbol of forked poisonous tongue cursing innocent passersby who do not drop a coin into his insatiate, “ever-empty bowl” and an “army of flies” trailing this “double-bent figure” of a mendicant. This serves as an indication of the fetid and odious character, and by extension that of a dissolute society that will only sprout thorns of discontentment.

“Woman of the People” (p.30) comes across as poem that paints the character of strangely potent and decadent beauty. The woman of the people is portrayed as collector of male conquests, a romantic, deviant, sexual vagabond with trysts all over the length and breadth of the country with the powerful and all. A “beauty of beauties”, mermaid-like, with “serpentine locks”, “Lethe-filled lips”, a “loom that spun lives” and a mistress that “enslaved nations” and made their “presidents bow to her” at will, a Helen of Troy come from a Hellenic past into an African present day version of the myth, maybe! She sweeps along with a corrosive and corrupting power to make all bow to her; but it is an intoxicating force that in the long run, akin to addictive drugs, does not spare even the bearer. Not surprising then that she ends up looking so cadaverous, plagued by a clueless malady or substance, and we are left to speculate the fading and wilting as being the fruit and wages of her decadence. As for the “Princess of Thieves” she reincarnates the “Woman of the People”, but in a more criminal and masculine fashion who, as we are told, plays “celebrated baddies”, “plays the bandit”, comes to town with her “band of merrymakers” and foments a reign of raining banknotes (p.41)

The climate of social violence is captured in Fragment IV. This is an episode of nocturnal violence where the tranquility of a silent lunar night soon degenerates into that of a thunderous, brutal aggression:

Like drumbeats, throbbing hearts rival sounds of the wild

Voices unvoiced at vespers, silence

Echo of footsteps passing and re-passing –

Knock, upon whose door did they not

The tired wood gave in after the thunder at the door

They beat the beast, in the form of guts, as best as they could

In-spiked their meaning

The voice of Violence rang (p.34)

This illustrates in the whole physically violent society where agents of the underworld, better defined by the poet as “Cadavers of civilization” in their “sinister visitation”, come under the cover of dark, brutally wreck open the tenants’ wooden doors and bestially beat the hell out of the victims. Going through today’s “deeds and misdeeds” or “faits divers” columns of Cameroonian newspapers, this depiction of violence and aggression has become incontestably recurrent grist, especially in urban settings. The violent nature of our society is not just physical; it is equally verbal as seen in the “Mendicant of Yeruwa” whose forked tongue viciously slices the air with curse and invective.

Hypocrisy as part of the prevailing moral decadence and bankruptcy, comes through in “Princess of the Thieves” when the poet lambasts the “celebrated baddies”, reliably identifiable with both our local economic feymen (conmen) and unscrupulous thieving politicians, who come announced by “banners and praise-songs” and the persona blatantly tells them:

…you are nothing of the legendary hero

You rob the poor and give them back

In the name of charity.

Banknotes rain during your reign – nothing

New to us, (p.41)

Still rising from the deep miasma of discontent, like nightmarish vapor breathed out and up from malodorous cavities into a lavender night, are baleful themes and images of the ghastly and the occult. The aptly titled “Festival of Darkness” is witness to the thematic gothica of this poetic and social experience. Hear the poet introduce into the scene the phantasmagoric aliens that people this clime of malcontents:

Washed-out mongrels dance

During the festival of darkness

Empowered by walls of agony –

Their triple human size mirror

Sanguinary depths (p.24)

The spectacle of horror is instantly and palpably conjured via the imagery of triple human size mongrels dancing in a tenebrous festival, markedly suggestive of an occult sanguinary ritual empowered sadistically by walls of an agonizing world, a world of beings whose blood the “wasted shadows” with “narcissistic forms” gamely thrive on. As the poet further intimates, these charm-using, gargantuan mongrels practice their macabre craft on an “oasis turn[ed] envenomed as private hell prowls” and with utter cannibalism “wait to engulf [their] own/in Makuru-like nightmare scenes” (p.24).

In this poem the author is fully transporting and immersing the reader in a realm of sheer metaphysical violence, a dehumanized and dehumanizing constituency that poetic imagination, with unapologetic hyperbolism, takes recourse to in order to present and represent the infernal absurdity of an insufferable ambient reality. Look around you today and question present actuality with regards to the issue of ritual slaughter and the trafficking of human organs, and you will pierce the metaphoric veil of the poet in this poem of gore. When leadership fails into abysmal depths of this tragic, dehumanizing absurdity, the state of affairs is better mirrored and indicted by a poet’s fertile and constructive imagination, all in a spirited bid to raise consciousness about, and if possible correct, the condition of those malcontents spawned by such failed leadership.

The segmentation of the collection offers a whole portion to Elegies. This is significant. These are homages rendered to the departed, both recognizable and not. On the reverent roll we identify Bate Besong (BB) associated with his venerable compeer, Christopher Okigbo, and hear his warrior name and feat sung in the elegiac praise-poem, “Obansijom Warrior”. The poet, at same time, grieves the loss and extols the feat of the “Two-legged brain, transcendental transcriber/ Contiguous of earth, monsieur”, the “Lone conqueror” who “still wages battle” in his death and dares the “lions’ den”, the “precursor” with a “trenchant tongue”! (pp 51-52). This is a rich harvest of befitting and deserved praise-words for the fallen poet-dramatist of national repute whose fiery political temper and courage was/is a representative, dissenting voice of the malcontents. His atypical talent and commitment raised his person, writing and his media interventions to a level that matched poetic fact with dramatic act. Our present persona mourns this loss, a compelling voice silenced by a mortal highway accident, though positively consoles himself that the battle is still being waged, surely through his works.

Beyond BB, other more private losses are grieved, like “Broken Flower” (dedicated to Mbah Sonia) whose “broken smile/the lackluster moon reflects”, whose loss is like a “ fit of lachrymose with a touch of black/[that] Lacerates the soul deeper than the eagle’s claw” (p.53). This stitches a series of powerful, poignant imagery that fits the occasion of sentimental loss suitably. At this juncture and rate, I am tempted to say that the poet in matters of heart and soul tables, aesthetically, a more accomplished gift than he does in his strictly political poetry. Amongst the eminent for whom the elegies have been penned, we find Michael Jackson in “The Day Music Died”. The poet indignantly prosecutes two cruel culprits in the events surrounding the artist’s demise. The first is falsehood:

Festooned Neverland

Once sought, found. Needless

To say that the kiss of falsehood

Can’t touch you here. (p.54)

From actuality, the poem is referring, chiefly, to the infamous ‘falsehood’ that dragged Jackson to court and saw his health, energy, morale, name, career and means sapped by the unrelieved agony of the criminal case that the lies had incited . The second culprit is the shameless media exploitation of Jackson’s woes and death:

They were all there – the

Gold and story diggers –

Those who broke you (p.54)

The diabolic mammonism of the indictments somehow converge into soulless exploitation because the dark mouths of lies and the yellow hands of sensation all had one grimy intention: to spin lucre out of Jackson’s body and works. This maddens the poet who is calling for a more ethical and a less materialist, money-minded society that neither suffers the living body with lies nor desecrates the demised body with the salacious. Implying from the persona’s caustic tone in their regard, they have participated in fomenting ethical and moral discontent not only in Jackson, but also among his innumerable fans and sympathizers.

Dzekashu MacViban at the 2012 Kwani Litfest in Nairobi. Photo Credit: Feling Capela.

In the ecopoetic elegy, “Rethinking the Land” (dedicated to Mahmoud Darwish), the poet collapses the dualistic differentiation between “man and nature”. In grieving the loss of Darwish, he mourns the death of the land/nature. Man and nature are fused into one heightened respect for the first ecological principle that everything is interrelated and interdependent on everything else. It is on this principle that the virtuous ecological cycle and its equilibrium are idealistically founded. Let’s hear the persona himself explicit, with poetry, the foregoing:

The heritage of loss belaboured, you

Carried their burden – our burden

On your back, as if your life on it depended –

Thunder grumbles over the land which

You said was – unfortunately, the Promised Land…

Do not wonder why nature is so chaotic

It is but a-mourning…(p.55)

There is an interrelationship of loss and mourning between the poem, the dedicated subject and nature/land. The poet mourns man and nature, nature in turn is a-mourning chaos caused on her, and this is the very nature the dedicated subject of the poem has mourned and reconstructed when he “saw the conflictual ruins [of now extinct vineyards, i.e. nature]/And built hope” (p.55). And this hope he built by logically continuing the collapsing “conflictual” oppositions between “word and world”:

Your word-world spun wonders of the land

Long forgotten in the face of neo-barbarism (p.55)

Therefore, the whole poem comes across with the meaning that and driving argument that with essential compassion and humility towards nature/land, we can (among other eco-compatible behavioral agencies and strategies) through the word save the world, that is if we develop an ecological ethic that ties with the primordial ecological principle stated above. Because: a mourning nature, “carrying its burden – our burden”, only begets a discontented world with its consequent multitudes of malcontents.

Content of Contentment

Here we cusp positive themes of bravado, optimism, peace, beauty, love and cornucopia, yes, themes that inspire the quest for and possibilities of contentment or bliss, and as such opening a vein distinguished by the positive determination and spirit of the scions, sired from the darkness of the malcontents, to succeed, to shine and to bear the flame of hope.

The theme of resistance to political oppression constitutes the eponymous poem, “Scions of the Malcontent”, (dedicated to Kangsen Feka Wakai, another compeer and wunderkind lately plauditted by the fastidious Bate Besong), which the poet crafts with a very sophisticated diction, phraseology and turn of style. Here we are before a repressive inquisition which through selected referential ‘autodaféism’ (in ancient Europe, ‘tumultuous years of the inception’ of democracy in Cameroon) compress time and space:

You have known them

Right? Those moments when angst

Was the unseen visitor, gelatinously gyrating

Those cold walls bespeak of defiance

(a toast to the muse of defiance

In this age of neo-auto-da-féism) (p.28)

There is the insidious skulk of the invisible, creepy visitor who is ‘gelatinously gyrating’, hinting as such at the sinister personification of the inquisitor. But his presence today is met by a generation of scions who, from being inhabited by a sort of angst, make a toast to the muse of defiance against despotic (neo)autodafé(ism). This spirit of defiance works and cows the inquisitors leading the poet to ask with mordant sarcasm:

Why do these pseudo-inquisitors tremble

At the mention of our names?

Aren’t they supposed to be godly,

unafraid of those they persecute? (P.28)

This militancy indicates the spirit of the new generation that poet seems to direct, despite the odds, towards a trajectory of resistance – the engagement of the content of containment of the vicious as a path to contentment – and not that of dark despondency, resigned defeat and sterile whining.

The above-mentioned resistance is martially emphasized in “Existence” by the determined and valiant declaration of the scions that:

We fought back, with light, the endless night

You imposed on our existence

…..for everyone who fell

Two rose – stronger. (p.13)

This bravado and battle-hardiness depicted and praised here imprints the signature of the new generation called upon, if it’s to continue to live in harmony with nature, to assume a combative mind-frame in the face of “asphyxiating embraces full of thorns” and the terrible, and certainly Western imperial empire with its faces of “decadent beauties in free fall” (p.13).

The optimistic breeze that blows in this collection, apart from brave resistance already pinpointed, can be seen as touching the flowers and fruits of peace, love, beauty and cornucopia. These elements and moods interweave themselves, and at times inextricably, in some of the poems, especially the love poems found in the segment christened ‘Are you Aphrodite’s Daughter?’ This segment contains some of the most stunning and lasting poems in the collection. They contain very elegant, romantic, accessible and memorable pieces. This style ties appositely with the turns and twists of associated optimistic themes mentioned above. “Our Time in Eden”, though short in time and tragic in ending (from an inexplicable tragedy not arising from the personae’s making), the edenic sojourn is full of idyllic, amorous and cornucopian imagery:

My eve and I, from twilight

We had magic hours, so short

……………..

My eve and I, beyond legendary affection

In Eden where we lived well –

…living to perfection. (p. 45)

The couple lived blissfully in strict obedience of established laws as they “sought no forbidden apple” and “feared the hell that would ripple” if they dared to. They effectively played their own responsible role of compliance before “some machination befell” them enigmatically and sent them roaming, estranged. As if to compensate the injustice visited the lovers in Eden; another cornucopian, idyllic and romantic episode seems to have converged their wandering paths in “Elsewhere”(p.46), a place dreamt of “beyond Utopia”, and continue their blissful romance, a place where the time is still and where “Quietude flows, spiced by… poetic whisper.” The persona-lover is thrilled by the delightful experience and asks, overwhelmed:

Is it surprising that I find comfort

In the sacred symphony of this place

And in the luster of your eyes? (p.46)

Apart from the sublime beauty evoked by luster of the lover’s eyes above, there is also a lush presence of other forms of the beautiful. For instance in the very sophisticated poem “Fragile” there is the evocation of feral beauty, where the poet is marveled and cries out in wonder about “Who can tell of the world/ that lies beneath her savage beauty” (p.47).

Threading the line of positive themes rising from the murky waters of discontent to express a better, happier world, we have the theme of optimism that inspires the poem “Muses”. Here we are presented with a condition of dawning possibilities where “Dreams are turning into realities” and sum up in a unique goddess “whose aura brings soothing” and “whose smile inspires/Eternally,” (p.48). The possibility of deliverance is prayed for in “Exodus” where the poet appropriates the biblical myth of the liberation of Israelites and locates it in contemporary condition, a condition where they have “lived in death” and that of matrimony gone irretrievably awry. What marriage is this that has held this people in bondage as were the Israelites in Egypt? Is the poet, from Anglophone prism and experience, borrowing from Epie Ngome’s What God Has Put Asunder? No matter the interpretative spectacles worn, the poet positively concludes the poem with their reaching “the land for which [their] hearts beat”, their “Promised Land” (p.14). Yes, the cornucopia overflowing with milk, honey and redeeming peace. The land of the contented. Should we dare to conclude that on the poem’s behalf?

Having gone through this dialectical exploration and dissection of MacViban’s collection, we must accept that there are still other analytical or critical possibilities. For instance, as suggested earlier, these poems do also exhibit hybrid textures that do not easily yield to the above diametrical dissections. We can total them up as those possessing an “Ambivalent Complex”. But then, this stimulating analytical matrix can be grist only for another day.

For today we can only meditate the condition of the malcontents and delight on the optimism and audacity of their scions as drawn and deciphered from both text and graphics. The collection, as you can read from the blurbs, is a “kaleidoscope of tones and tunes, of styles and guiles”, “at once palatable and dense”, and coming from a young poet possessing “one of the most resounding new voices on the Cameroonian poetry landscape”. What more can be said about this maiden collection? Well, one more interesting thing to say after the superlative encomiums, is about the few loose hair-strands that spoil the poetic soup.

Here we go. The culpabilities are variably shared by the poet and his editor/publisher. But I most first gore the aesthetic ass of the muse. He takes first responsibility for the mess, I believe so. That said, the poet seems to have an intractable appetite for overkill: if it is not the pardonable echoes of TS Eliot here and there (until I picked the echoed to re-echo the fact earlier as witnessed supra in this review’s cynical mimicry of the Eliotian voice).

There is also the deafening or numbing lexical massacre of “piercing” with sounds piercing the night, two voices piercing each other or the shout of joy piercing the firmament. (Really, I feel the fierce piercing sounds ruin my tympanum). Again if it is not the pointless excesses of the archaisms with odious bespokes/bespeaks, Los!, nays, then it would be the useless cliché-ridden many-an-eye, many-a-one and other many-a-this-or-that, my goodness, can’t a poet just live and sound in the present and be! Before you end with that archaic linguistic past, the author-poet, without restrain, is already in a libertine indulgence with grammatical and rhythmic heresies taking arbitrary and insensitive liberties with punctuation, line breaks and flow. This reckless, truncated poetic riding punctures the joys of music, drama, sculpture and atmosphere generated by the craft of a keener ear and a more disciplined hand. The editor/publisher should really have stepped in here like elsewhere and polish the diamond.

And it would not, too, have been in the following that the latter would have restrained from guiding the poet towards a more burnished outcome. I mean the observably truncated and incoherent poetic narrative that is occasioned, not solely by grammar and rhythm, but also by imagistic discontinuities. Though the collections sparkles with arresting images and lines, they sometimes remain sporadic sparks of stars that hesitate to cluster into an integral, definable galaxy. In short, there should be a threading consistency, within a poem, of the chosen images and figures that can be plausibly woven in from all possible and potential ramifications to prove they should belong to the so titled poem or related poem and nowhere else.

In guise of conclusion, it must be reiterated that in spite of the above inadequacies, the book remains a fascinating collection of poetry that has already been applauded. Now that we have closed Scions of the Malcontent, may we then wait for Poetry is Dead? Tell us, Sir.

Where can I get this?